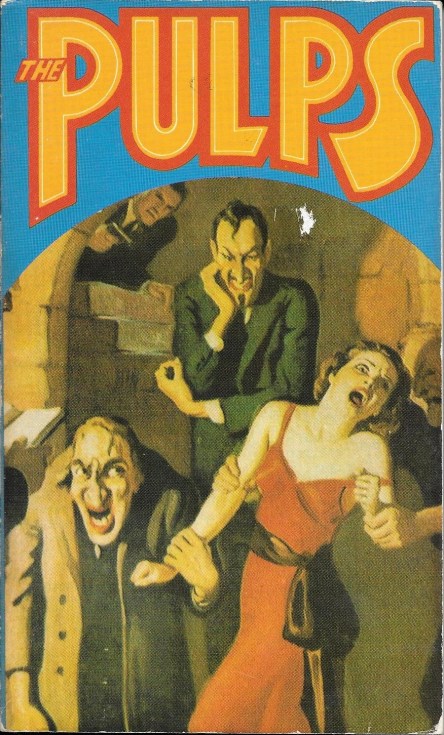

Although in the popular imagination, Robert E. Howard (1906-1936) continues to be identified as the creator of Conan the Barbarian and a pillar of the sword and sorcery tradition, readers who have explored beyond Conan (or approached Howard from a different avenue, as I did) know that the prolific pulp writer also frequently indulged in horror in a variety of styles. Indeed, horror is a critical ingredient even of Howard’s heroic fantasy, and almost all of his work is streaked with terror.

Consider the foes, both monstrous and supernatural, that Conan and Howard’s other he-man heroes faced in their adventures (the gray ape that silently stalks Conan in a night-black dungeon in The Hour of the Dragon is typical, and it goes without saying that magic in Howard’s stories is rarely benevolent), and it becomes clear why it can be difficult to sort Howard’s “horror” tales from his other output, and why there is so little overlap between different collections.

This article focuses on four different paperback collections of Howard’s horror stories, comparing their contents and taking note of different editorial priorities. They are far from the only collections of Howard’s work, and no slight is meant against (for example) the pioneering paperback collections edited by Glenn Lord. The editions under discussion are, however, either in my possession or readily available, and each is different enough to warrant investigation. (Complete contents of each book are listed at the end of the article.)

My first encounter with Howard’s fiction was through Baen Books’ Cthulhu: The Mythos and Kindred Horrors, edited by David Drake. As I have written elsewhere, I actually had a hard time tracking down H. P. Lovecraft’s fiction when I first heard about it as a budding middle school fantasy enthusiast. His “Cthulhu Mythos” had for me at the time the same enchanted, mysterious quality that the Necronomicon had for his characters: something about which obscure references were dropped but which remained tantalizingly out of reach. The Mythos and Kindred Horrors was thus a welcome discovery, and the short story “The Black Stone” which leads off the book was the first proper Mythos story I was able to get my hands on.

Although short, The Mythos and Kindred Horrors remains a fine introduction to Howard’s macabre imagination: as promised, it contains a number of significant Mythos stories, including “The Black Stone,” “The Fire of Asshurbanipal,” and “The Thing on the Roof,” but also examples of his dark, violent fantasy (“The Valley of the Worm,” “People of the Dark,” and “Worms of the Earth”) and even a weird Western (“Old Garfield’s Heart”).

The final story, “Pigeons From Hell,” is a truly terrifying slice of Southern gothic, and like the greatest horror stories earns its scares as much from the depths of moral depravity it displays as from atmosphere or shocks (Stephen King named it “one of the finest horror stories of our century” in Danse Macabre). “Pigeons From Hell” was adapted into a 1961 episode of the Boris Karloff-hosted anthology show Thriller, an adaptation that, while effective, shows a clear debt to Psycho, released the previous year. Resetting it in the modern South made the horror more immediate, as if the two guys from Route 66 had stumbled onto the Bates Motel, but the abbreviated runtime strips out the racial element that gives the original story so much of its charge, even removing the final twist.

Another volume, and one that specifically includes only Howard’s Cthulhoid fiction (so no “Pigeons From Hell”), is Nameless Cults, edited by Robert M. Price. Presented by Chaosium, publisher of the Call of Cthulhu role-playing game, Nameless Cults is part of the Call of Cthulhu Fiction series: Chaosium publishes numerous volumes of fiction to supplement its game and to present the works of Lovecraft, other members of his circle, and contemporary authors in accessible editions; some are organized around a single subject or a specific deity or aspect of the Cthulhu Mythos, others by author, as in the case of Nameless Cults.

The title refers to one of Howard’s own contributions to the Mythos, the “Black Book” Unaussprechlichen Kulten by Friedrich Von Junzt, the author’s answer to Lovecraft’s forbidden tome the Necronomicon. Embroidering on his friend’s growing set of references, Howard added Von Junzt and his book, along with such characters as the “mad poet” Justin Geoffrey and the Great Old One Gol-Goroth, to the Mythos. (Howard’s many pre-historic speculations on Atlantis, Valusia, and other aspects of Conan’s “Hyborian Age” would also be swept into the Mythos by Lovecraft and others in a pattern of mutual borrowing, so one could as easily refer to a “Weird Tales Mythos” as use the more familiar term “Cthulhu Mythos,” which of course was a label added only later by Lovecraft’s literary executor August Derleth.)

Price’s editorial remarks lend extra value to Nameless Cults; in addition to providing detailed information about the provenance of the stories included (some of which are fragments that have been finished by others), Price puts them into context as both a scholar of both Lovecraft and a theologian (Price has edited many of Chaosium’s books, as well as publishing books and articles on Christianity and editing Lovecraftian journals such as Crypt of Cthulhu). The most important insight Price brings is his consideration of the Mythos as a loose collection of themes and references rather than a continuity that must be reconciled and kept free of contradictions (as with fellow scholar S. T. Joshi, much of Price’s work has involved debunking Derleth’s spurious claims on behalf of Lovecraft and his creations, but in general Price’s perspective is more sympathetic to a multi-faceted rather than a purist approach). It’s this freedom that allows writers of different temperaments to make use of the Mythos and gives it the feeling of an actual mythology, scattered and secret but nonetheless organic.

It’s hard to think of a writer more different in temperament from H. P. Lovecraft than Robert E. Howard, at least as revealed in their stories. Lovecraft’s protagonists, to the extent that they are developed as characters at all, tend to be inward-looking scholars or antiquarians, drawn inexorably toward doom by curiosity or forces they do not understand. (An exception is Professor Henry Armitage, the hero of “The Dunwich Horror,” who is able to take charge and push back the demonic entities seeking entrance to our world.) Howard, however, puts the same kind of fearless, action-oriented warriors who populate his other stories into his horror tales (whether in a historical or fantasy setting or the contemporary world, the defining characteristics of Howard’s heroes are hyper-competence and a willingness to take action for what they believe is right, regardless of the cost–still the formula for an action hero today).

The contrast is amusingly illustrated in “The Challenge From Beyond,” a curious multi-author collaboration included in the Chaosium volume. At the end of Lovecraft’s chapter, the protagonist finds that he has been–horror of horrors!–transformed into “the loathsome, pale-grey bulk” of an alien centipede, and faints dead away: a typical Lovecraftian ending. As Howard picks up the thread in the next chapter, however, the hero’s perspective has changed and he begins to revel in the power of his new form, as “fear and revulsion were drowned in the excitement of titanic adventure”:

What was his former body but a cloak, eventually to be cast off at death anyway? He had no sentimental illusions about the life from which he had been exiled. What had it ever given him save toil, poverty, continual frustration and repression? If this life before him offered no more, at least it offered no less. Intuition told him it offered more–much more.

In Howardian fashion, “The Challenge From Beyond” changes from a story of horror to one of triumph, as the protagonist uses the strength of his new form to conquer the aliens and make himself their king, “a Conan among centipedes” in L. Sprague de Camp’s memorable phrase.

The physical bravery and strength that Howard considered so essential to being a hero (or a man, at that) actually tends to prop up the horror effects in his Cthulhu stories, however. The darkness is all the more terrifying when even such specimens cannot hope to defeat it; at best, victory means simply surviving. (It is unsurprising that Lovecraft’s “The Dunwich Horror” was a favorite of Howard’s, and its formula of investigation and action would prove a useful model for his occult detective fiction. It’s also, not coincidentally, the Lovecraft story that most resembles a Call of Cthulhu game scenario.)

The Haunter of the Ring & Other Tales, edited by M. J. Elliott as part of Wordsworth Editions’ “Tales of Mystery & The Supernatural” series, includes the best-known of Howard’s Cthulhu Mythos stories but also casts a wide net, including other horror and dark fantasy stories that cover a variety of subject matters and styles. Several of these stories, such as “In the Forest of Villefore” and “Wolfshead” (part of a werewolf cycle), are among the author’s earliest published works and show a still-raw talent. The volume also shows the range of genres that Howard explored in search of outlets for publication and introduces some of the author’s recurring characters: occult investigator John Kirowan and detective Steve Harrison, for example.

It also provides examples of Howard borrowing from his literary forebears and contemporaries: one of my favorites, the short novel “Skull-Face” (included in both the Chaosium and Wordsworth editions), is an entertaining pastiche of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu novels with the fantasy elements dialed up. Instead of the Chinese doctor, the titular villain is a survivor from the ancient past with scientific knowledge so advanced that it might as well be magic. (The hero of “Skull-Face,” Stephen Costigan, is not to be confused with another Howard series hero, Sailor Steve Costigan, but is an example of what Elliott describes as Howard’s “inexplicable fondness for certain character names.”)

If “Skull-Face” is Howard’s version of Rohmer, reading a number of Howard’s stories in close succession makes clearer the influence of other authors, even as in the best of his stories Howard’s own personality shines through. Even beyond its Mythos trappings, with its antiquarian protagonist and dreamy atmosphere “The Black Stone” is clearly modeled after Lovecraft, as Howard acknowledged in his own letters. Similarly, “The Dream Snake” and “The Fearsome Touch of Death” are indebted to Ambrose Bierce, with the implication that it is internal fears, not external threats, that are most destructive.

As Price points out in his introduction to Nameless Cults, the author who influenced Howard’s horror output most strongly besides Lovecraft was the Welsh Arthur Machen. In a number of Howard’s stories touching on reincarnation or racial memory and characterizing the “Little People” of myth as monstrous survivors of a pre-human race, “he has gone back to one of Lovecraft’s own sources, Arthur Machen, and remixed the Mythos, turning up the volume on the Machen track.”

Indeed, the recurring theme that unites both the stories of Conan, Pictish king Bran Mak Morn, and flashes of racial memory with his stories of the Cthulhu Mythos is the long shadow cast by the distant, prehistoric past, “Lurking memories of the ages when dawns were young and men struggled with forces which were not of men” (in the words of “The Little People”). Just as it was for Edgar Rice Burroughs, another important influence on Howard, that struggle against wild nature and subhuman savagery was a defining one for both character and narrative, and as with Burroughs it sometimes manifested in Howard’s work as a racial scheme in which tall, white-skinned, “clean-limbed” Aryans (a term borrowed from the anthropology of the time, but which is particularly regrettable with modern hindsight) swept Westward throughout Europe (and later America), routing the short, swarthy tribes that became the basis for legends of goblins and the hidden races of Machen, Lovecraft, and others. (But as Price points out, Howard was able to have it both ways by making the underdog Picts into heroes pitted against an even older, more secretive and less human race, as in “Worms of the Earth.”)

In these stories and others, the modern reader runs headlong into Howard’s sometimes objectionable racial characterizations: stories set in the deep South and Southwest include epithets for black and Mexican characters, sometimes in dialogue, but sometimes as part of the narration or from the viewpoints of characters who are supposed to be sympathetic. As in my discussion of representation in the serials from the same time period, it is pointless to pretend that such attitudes and words weren’t part of the world of at least some in Howard’s time, and pointing out parts of Howard’s work that haven’t aged well need not imply a disavowal of the strong parts of his fiction.

And perhaps it is simply my modern perspective, but I think it is telling that in general Howard’s strongest stories take a more nuanced point of view, with characters of all races showing both good and bad qualities. As Rusty Burke points out in his introduction to Del Rey’s The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard, the interaction of common racial prejudices in Howard’s native Texas with the author’s natural sympathy for the underdog and belief that ultimately a man is what he makes of himself led to some complex characterizations. The flip side of his often-stated distrust of civilization and its stultifying effects, Howard showed great admiration for native peoples who (in his admittedly romanticized view) lived close to nature; one of his wisest characters was the African “medicine man” N’Longa, friend and advisor to Solomon Kane.

The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard is the longest (over 520 pages) and most comprehensive collection at my disposal, and yet even it omits stories that may be found in the others (“Skull-Face” is the most notable absence, possibly left out because of its length). It does, however, cover the broadest range of Howard’s output, including Cthulhoid horror, sword and sorcery, regional horror (Western and Southern, including “Pigeons From Hell”), and contemporary adventure stories, as well as samples of Howard’s seafaring, boxing, and detective fiction.

The Del Rey volume also includes four unfinished stories, grouped as “Miscellanea,” and there is more bibliographic detail than in either the Baen or Wordsworth volumes, listing first publication (or manuscript source in the case of posthumously discovered stories) and detailed notes on changes in spelling or punctuation made by the editor.

It is also the only volume to include more than a few of Howard’s numerous poems. Like his fellow Weird Tales contributors H. P. Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith, Howard was a prolific versifier, and like them he remained largely conservative in the face of modernism, sticking to rhyming, metric poems. Most of his poetry has a rough-hewn, deliberately “barbaric” quality, often cast in multi-stanza ballad forms with rhyming couplets: appropriate for his subjects, usually as dark and gruesome as those he favored in his stories. Although it is unlikely that Howard’s poems will ever be popular outside of weird fiction (and heavy metal) fandom, they contain some vivid and concise images, such as the following lines in “Dead Man’s Hate”:

There was no sound on Adam Brand but his brow was cold and damp,

For the fear of death had blown out his life as a witch blows out a lamp.

It is often treacherous to psychoanalyze a writer based on their fiction, but to an extent horror writers invite it: the best are not simply calculating what they think will scare their audience, but are delving into and externalizing their own fears. That’s not to say that horror writers necessarily believe in what they’re writing (crackpot theories that Lovecraft possessed secret knowledge of real-life Cthulhu cults notwithstanding), but their choices can be revealing.

Robert E. Howard’s own tragic story (he committed suicide at age 30 after his mother slipped into her final coma) is at odds with the implacable supermen he created, but even in his stories he often hinted that death was preferable to a life of pain or defeat. Elliott singles out a passage in “Skull-Face” in which recovering opium addict Stephen Costigan ponders drowning himself, “that I should soon attain that Ultimate Ocean which lies beyond all dreams.”

The stoicism with which Costigan considers ending his life is of a piece with the pragmatism and toughness of most of Howard’s characters, but there is another side to Howard that tends to be overlooked, the dreamy, “feminine” side that gave us the “mad poet” Justin Geoffrey. Geoffrey is often seen as a portrait of Howard’s friend and correspondent H. P. Lovecraft, and he does resemble Lovecraft’s typical protagonists, often so removed from this world that their weird art or poetry are perfect channels for the “outside” influences of the Cthulhu Mythos to find their way in. Nevertheless, if, as Lovecraft himself argued, “the real secret [of Howard’s characters] is that he himself is in every one of them,” then Geoffrey is certainly a facet of Howard’s personality. Robert M. Price goes further, saying of Geoffrey,

Here is Howard with a vengeance, the real Howard in a far deeper sense than either Balthus [“a realistic depiction of Howard compared with Conan, the idealized version”] or Steve Costigan. Justin Geoffrey is the archetypal Byronic artist too sensitive for this mortal coil, a frail human funnel for the whirlwinds sweeping down from between the stars.

Justin Geoffrey would die “screaming in a madhouse,” a fate that Howard possibly predicted for himself, and to which he found suicide preferable.

An even more revealing self-portrait can be found in the unfinished story “Spectres in the Dark,” included in The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard. In this fragment, unseen forces hiding in the shadows drive otherwise normal individuals to commit murder. One such unwitting killer is Clement Van Dorn, an artist who finds himself accused of killing his mentor. Visiting him in jail, Van Dorn’s friends find him in a pathetic state:

Clement nodded but there was no spark of hope in his eyes, only a bleak and baffled despair. He was not suited to cope with the rough phases of life, which until now he had never encountered. A weakling, morally and physically, he was learning in a hard school that savage fact of biology–that only the strong survive.

Suddenly Joan held out her arms to him, her mothering instinct which all women have touched to the quick by his helplessness. Like a lost child he threw himself on his knees before her, laid his head in her lap, his frail body racked with great sobs as she stroked his hair, whispering gently to him–like a mother to her child. His hands sought hers and held them as if they were his hope of salvation. The poor devil; he had no place in this rough world; he was made to be mothered and cared for by women–like so many others of his kind.

That Robert E. Howard’s career was cut short by suicide, just as the author was developing his voice and was about to see his work published outside of the pulps, is a loss for readers. That he felt so compelled to end his own life was a tragedy for him. Perhaps the most fitting conclusion is in the words of David Drake, editor of The Mythos and Kindred Horrors, among the first words about Howard that I encountered:

Robert E. Howard had the personal misfortune to spend most of his life in a place where black hatreds ruled everyone; where currents of violence so closely underlay the surface of ordinary existence that a snub, a woman, or the ethnic background of a chance acquaintance was apt to bring a lethal outburst; where a man’s only path to respect was through strength and his willingness to use that strength.

Drake is referring, of course, not to West Texas, where Howard lived, nor even the fictional Hyboria that Howard set down on paper, but the interior of Howard’s mind, “a grim, dark place,” from which writing tales of adventure, fantasy, and even horror allowed Howard to escape . . . for a time.

Appendix: Contents of editions under discussion (titles in italic text indicate poems)

Cthulhu: The Mythos and Kindred Horrors

Edited and with an introduction by David Drake (Baen Books, 1987)

Arkham

The Black Stone

The Fire of Asshurbanipal

The Thing on the Roof

Dig Me No Grave

Silence Falls On Mecca’s Walls

The Valley of the Worm

The Shadow of the Beast

Old Garfield’s Heart

People of the Dark

Worms of the Earth

Pigeons From Hell

An Open Window

Nameless Cults: The Cthulhu Mythos Fiction of Robert E. Howard

Edited and Introduced by Robert M. Price (Chaosium Call of Cthulhu Fiction, 2001)

The Black Stone

Worms of the Earth

The Little People

People of the Dark

The Children of the Night

The Thing on the Roof

The Abbey (w/ C. J. Henderson)

The Fire of Asshurbanipal

The Door to the World (w/ Joseph S. Pulver)

The Hoofed Thing

Dig Me No Grave

The House in the Oaks (w/ August Derleth)

The Black Bear Bites

The Shadow Kingdom

The Gods of Bal-Sagoth

Skull-Face

Black Eons (w/ Robert M. Price)

The Challenge from Beyond (w/ C. L. Moore, A. Merritt, H. P. Lovecraft, and Frank Belknap Long)

The Haunter of the Ring & Other Tales

Compiled and Introduced by M. J. Elliott (Wordsworth Editions, Tales of Mystery & The Supernatural, 2008)

In the Forest of Villefore

Wolfshead

The Dream Snake

The Hyena

Sea Curse

Skull-Face

The Fearsome Touch of Death

The Children of the Night

The Black Stone

The Thing on the Roof

The Horror from the Mound

People of the Dark

The Cairn on the Headland

Black Talons

Fangs of Gold

Names in the Black Book

The Haunter of the Ring

Graveyard Rats

Black Wind Blowing

The Fire of Asshurbanipal

Pigeons from Hell

The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard

Introduction by Rusty Burke; Illustrated by Greg Staples (Del Rey, 2008)

In the Forest of Villefère

A Song of the Werewolf Folk

Wolfshead

Up, John Kane!

Remembrance

The Dream Snake

Sea Curse

The Moor Ghost

Moon Mockery

The Little People

Dead Man’s Hate

The Tavern

Rattle of Bones

The Fear That Follows

The Spirit of Tom Molyneaux

Casonetto’s Last Song

The Touch of Death

Out of the Deep

A Legend of Faring Town

Restless Waters

The Shadow of the Beast

The Dead Slaver’s Tale

Dermod’s Bane

The Hills of the Dead

Dig Me No Grave

The Song of a Mad Minstrel

The Children of the Night

Musings

The Black Stone

The Thing on the Roof

The Dweller in Dark Valley

The Horror from the Mound

A Dull Sound as of Knocking

People of the Dark

Delenda Est

The Cairn on the Headland

Worms of the Earth

The Symbol

The Valley of the Lost

The Hoofed Thing

The Noseless Horror

The Dwellers Under the Tomb

An Open Window

The House of Arabu

The Man on the Ground

Old Garfield’s Heart

Kelly the Conjure-Man

Black Canaan

To a Woman

One Who Comes at Eventide

The Haunter of the Ring

Pigeons from Hell

The Dead Remember

The Fire of Asshurbanipal

Fragment

Which Will Scarcely Be Understood

Miscellanea:

Golnor the Ape

Spectres in the Dark

The House

Untitled Fragment