It’s nearly halfway through January, so I guess I should put together my thoughts on the films I saw in 2023. Usually I limit myself to films I actually watched during the calendar year, but most years I put this list together much sooner, and it’s not like I’m going to be audited or anything. This year’s list is even more genre-heavy than usual, reflecting both my preferences and the movies I got around to seeing. As always, however, there are films I would have liked to consider that got away from me (I’m hoping to catch up with Poor Things soon). Ah, well. Even out of what I did see, putting together a list and ranking my choices poses a challenge. I know, I always say ratings and rankings are bullshit, and then I go ahead and try to do it anyway. My Letterboxd diary lists everything I watched for the first time last year, and if you care to investigate you may notice that my star ratings don’t always match this list. So take everything with a grain of salt.

Worst Movie: I usually put miscellaneous categories after the main list, but we’re here to celebrate the good films of last year, so let’s get this out of the way: Cocaine Bear (dir. Elizabeth Banks) promised a trashy, gleefully offensive good time, but it was only intermittently shocking, with the bear attacks (fueled by bags of coke dropped into its forest by bungling smugglers) stranded in a limp crime plot. The attempts to pull our heartstrings with a pair of cute/precocious kids lost in the woods just made it more insulting. There is enough big-name talent involved in this (RIP, Ray Liotta) that you’d think they would aim higher than an original you’d see on SyFy or Tubi.

Biggest Disappointment: I didn’t expect The Super Mario Bros. Movie (dir. Michael Jelenic and Aaron Horvath) to be a masterpiece, but I had higher hopes than this. Nintendo has been gun-shy about allowing adaptations of its IP since Jankel and Morton turned 1993’s Super Mario Bros. into a cyberpunk flop almost entirely divorced from the game, but this animated film veers too far in the opposite direction, with every potentially interesting choice sanded down in the name of brand management. The result is weirdly airless and a little mean, with Mario (voiced by Chris Pratt*) ushered through the beats of a hero’s journey that takes him from a put-upon plumber to savior of the Mushroom Kingdom. Poor Luigi (Charlie Day**) hardly has anything to do, just like younger siblings handed the Player 2 controller everywhere. It’s low-hanging fruit to compare a CGI animated movie to video game cut scenes, but sequences of Princess Peach (Anya Taylor-Joy***) coaching Mario through an obstacle course and our heroes building karts for the inevitable chase make the comparison hard to avoid. Wreck-It Ralph hit these marks with a lot more grace and heart.

* ?

** Okay, this kind of works.

*** Yes, all the major characters are voiced by celebrities. At least Jack Black is having fun.

On to the ranked list:

10. One thousand years ago, the warrior Gloreth defeated a great beast, and ever since, the realm has maintained walls and an order of knights armed with high-tech weapons in case it returns. There’s a lot to like about Nimona (dir. Troy Quane and Nick Bruno): a setting that combines the contemporary and medieval in a way we don’t see on film very often, a queer perspective still rare in animation, and a strong sense of design. Add to that a compelling central character, a knight (Riz Ahmed) disgraced by a crime he wasn’t responsible for, and it starts strong. What I didn’t like very much was the title character, a bratty pink-haired girl (voiced by Chloë Grace Moretz) who attaches herself to the knight in hopes of joining his (imagined) villainy. I lived through the ‘90s, I don’t need any more edgy mascot characters with attitude. Fortunately, there is more to Nimona than the punk exterior—much more. She is a shapeshifter, a dangerous ally to have in a realm built on a foundation of paranoid fear of monsters. There is another side to the story of Gloreth and the beast, and it’s in the second half of the film, as the truth comes to light, that Nimona soars.

9. Like a lot of moviegoers, I did see both halves of the “Barbenheimer” event that gripped cinemas last summer, although I didn’t see them on the same day. Barbie (dir. Greta Gerwig) is superficially similar to The Lego Movie: it establishes the world of a beloved toy brand on its own visual and metaphysical terms, then burrows into its underlying psychology. It even features Will Ferrell as a corporate CEO, but Ferrell’s presence is a bit of misdirection, as the struggle Barbie (Margot Robbie) faces isn’t about asserting herself in the face of an overbearing father/boss figure, at least not directly. In Barbie’s world, serious political thought and nightly dance parties coexist easily, since in her multitude she is both President and DJ in addition to all the other careers she’s had over the years (multiple actresses play these different versions, all of them “Barbie,” but Robbie is the Barbie, as it were). Ken (Ryan Gosling) hangs on her every word and gesture, just hoping for a little bit of attention. Without Barbie around, it’s like he hardly exists. The plot gets rolling when Barbie starts to have disturbing, uncharacteristic thoughts—What is death? Why am I unhappy sometimes?—that shake the foundations of her perfect existence, setting her and Ken on a journey to the real world, where girl power isn’t taken for granted. Barbie comments on patriarchy, womanhood, and role models, and it sometimes threatens to buckle under the weight of so much meaning, but Robbie’s and Gosling’s performances are alternately hilarious and touching, and Robbie understands the assignment of playing a doll—essentially a cartoon character—who gradually learns what it means to be human. Think of it as Pleasantville in reverse.

8. Many science fiction films ask, “What if your entire life was a lie?” In They Cloned Tyrone (dir. Juel Taylor), small-time hood Fontaine (John Boyega) is ambushed and killed by a rival drug dealer, only to wake up in his own bed the next morning. Far from being a nightmare, his murder happened in front of other people who are surprised to see him up and about. Their investigation leads to a far-reaching conspiracy involving clones (duh), mind-controlling chemicals, and underground bunkers. On the one hand, this seems to remix beats and themes from Jordan Peele’s films (especially Get Out and Us), but without all the subtlety and ambiguity that make Peele’s movies so unsettling. On the other hand, Peele doesn’t have a trademark on black horror, and subtlety isn’t everything. Tyrone clearly has deep roots in the kind of conspiracy theorizing featured in blaxploitation movies like Three the Hard Way and parodied in Undercover Brother, and it leavens the action and weirdness with humor. Jamie Foxx as a vain, over-the-hill pimp and Teyonah Parris as one of his girls who wants more from life get most of the funny lines (as well as being active characters who keep the plot moving forward), but Boyega as a man of few words undergoing an existential crisis is the emotional center.

7. Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 (dir. James Gunn) brings the spacefaring subseries of the Marvel Cinematic Universe to a close, at least for now. While unable to totally escape the orbit of the larger MCU plot (particularly the replacement of Peter Quill’s lover Gamora with an angrier version of her from a different timeline who wants nothing to do with him), this installment provides as much information as is necessary for the trilogy to stand on its own. It mostly focuses on Rocket (Bradley Cooper) and finally explores his tragic history as a lab animal “uplifted” by the would-be godlike High Evolutionary before his escape. There’s a lot going on in this film as it ties up as many loose ends as it can, but it demonstrates again Gunn’s love for the weird byways in comics lore and shows why this oddball franchise has been such a good fit for him.

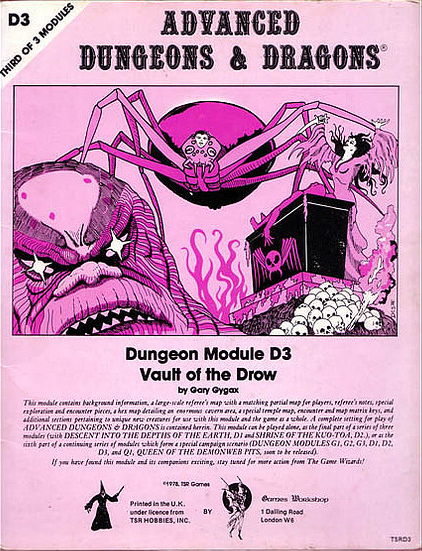

6. The Dungeons & Dragons game has never been one story, but rather a premise. Places, characters, and other conventions have been part of the official materials to the point that there is a recognizable D&D world distinct from other fantasy settings, but unless you’ve played it, you might only have a vague idea of tenth-level wizards and dark elves. Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves (dir. John Francis Daley and Jonathan Goldstein) brings the game to life better than any previous adaptation, deploying character types, monsters, and magic that will be familiar to fans but in a story that won’t leave non-players feeling left out. Chris Pine plays a disillusioned bard whose turn to thievery to provide a better life for his family resulted in tragedy. After finally escaping from prison with a taciturn barbarian warrior (Michelle Rodriguez), he regroups with his old comrades only to find one of them was behind the betrayal that landed him there in the first place. This is a fun, high-spirited adventure with real emotional stakes and (of course) a bigger threat to the world than is immediately apparent, giving the ragtag found family of thieves and outcasts a chance to become heroes.

5. Many of Hayao Miyazaki’s films involve work: even in the magical bathhouse of Spirited Away, those towels aren’t going to fold themselves. In The Boy and the Heron, the grief-stricken boy Mahito spends part of his sojourn in the other world catching and cleaning fish alongside a butch sailor (who, like many of the people he encounters, corresponds to someone from his regular life, but transformed). It’s not hard to read these interludes as metaphors for redemption, with the main characters finding space to work out their issues, but since I started working at a coffee shop this winter, I was struck by the literal truth of it as well. When you start a new job, you go to a strange place full of unfamiliar people and spend hours performing tasks whose meaning may only gradually become clear. Time passes slowly or quickly but with little relation to the outside world. And eventually you feel at home there and become part of the scenery for someone else. Given that Miyazaki doesn’t seem likely to ever retire, despite announcing that this would be his last movie, I think this is a feeling he knows well.

4. Where 2018’s Into the Spider-Verse introduced Miles Morales (Shameik Moore) and several spider-themed heroes from parallel dimensions, the follow-up Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (dir. Joaquim Dos Santos, Justin K. Thompson, and Kemp Powers) raises the stakes by introducing an organization of hundreds of such characters, and the real reason Miles hasn’t been invited to join them before. The eclectic, constantly-shifting animation style that made the first film so refreshing is, if anything, even more pronounced in this: as Miles and best friend Gwen Stacy (Hailee Steinfeld) spend time traveling between several different worlds, each one is rendered in a distinct visual style. The best part about this is that the trippy cosmic material is balanced by the emotional realities of the characters, their situations, and their motivations. It’s also, indirectly, an argument against the kind of schematic plot beats that make so many superhero movies tiresome, building to a daring cliffhanger ending.

3. In Suzume (dir. Makoto Shinkai), a schoolgirl follows a handsome wanderer to an abandoned town. When her curiosity leads her to open a door that releases a storm-like “dragon” and a mischievous cat spirit, she becomes entangled in his mission to keep the doors to the spirit realm closed. He also gets turned into a chair, which makes her help all the more crucial. Suzume is, obviously, a rather odd movie, but the magical realist plot turns are balanced by down-to-earth moments in which Suzume navigates her way across Japan by rail and ferry, finding friends and other helpful people along the way. The dragon stands in for the natural disasters that have struck Japan in recent years, but concentrating on one girl’s experiences, good and bad, keeps it from being too general.

2. God bless Wes Anderson. In the face of criticism that his work is too stagey and artificial, he doubles down and just keeps pursuing his own distinctive muse. Asteroid City is a frame within a frame: what at first appears to be a black and white television documentary gives way to staged scenes from the life of a playwright, with the central story—the dramatization of his play—designed and lit with the bright colors of a vintage postcard or schoolbook from the 1950s. The fragmentation of the story across these different layers—superficially about a diverse group stranded in a desert town after a UFO landing, but thematically about grief in all its forms—can be distancing, but Anderson has never been afraid to find the perfect settings for his jewels, whether those consist of close-ups, quietly devastating lines of dialogue, or carefully-composed scenes in their entirety. At this point, anyone lining up for an Anderson film knows what they’re in for. In the same year, he refined his hybrid staging even further with four adaptations of short stories by Roald Dahl for Netflix, with actors reading the narrative and switching to dialogue or action as Dahl’s text dictates, within sets combining moveable flats and real locations. My favorite of these was The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, the longest and most involved of the four and also the first one that was released.

1. It could be said that aspiring teen stuntwoman Ria (Priya Kansara) lives in her own world, and neither setbacks at school nor discouragement from her parents shakes her faith in herself. But when her older sister, art school dropout Lena (Ritu Arya), becomes engaged to a seemingly perfect guy, Ria believes that Lena’s been brainwashed into giving up her dreams and selling out, and she takes it upon herself to stop her. Ria’s campaign against the marriage leads to an escalating series of tactics, from attempts at persuasion to digging up dirt on Lena’s fiancé and planting evidence. She may have crossed the line, but what if she’s right? Polite Society (dir. Nida Manzoor) is a hoot, an energetic martial arts comedy (and, with They Cloned Tyrone, the second movie on this list to namecheck Nancy Drew) and a rousing affirmation of sisterhood set in the distinctive milieu of the Pakistani British community.

0. Oh shit, the hits keep on coming. The other half of the “Barbenheimer” duo, Oppenheimer (dir. Christopher Nolan) is arguably more straightforward than any of Nolan’s recent films, but even so it features multiple timelines and shifts of perspective that threaten to drop the floor from beneath the audience. The race to build the atomic bomb is interlaced with a security hearing a decade after Hiroshima, by which time physicist and project leader J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) had become a scold of the international community, lionized but racked with guilt. The result is a portrait of a complex, conflicted man who was skilled at political operation, but ultimately not as skilled as he imagined.

-1. See what I did there? Godzilla Minus One (dir. Takashi Yamazaki) was my favorite movie of the year, and one of the best films of the entire Godzilla series. The title sets it up as a quasi-prequel, not quite in continuity with the 1954 original but in dialogue with it. As the story begins, Shikishima (Ryunosoke Kamiki), a Kamikaze pilot, lands on an island base for (unneeded) repairs to his aircraft. That night, the local sea monster attacks and Shikishima jumps into his grounded plane but is unable to pull the trigger of his forward guns. He survives but everyone else on the island is killed. Thus Shikishima is haunted by his two failures to act, and when he returns to a defeated, ruined Tokyo, he is shunned as a deserter. Even when he gets a job on a minesweeping boat and enters a tentative relationship with a young single mother (Minami Hamabe), he cannot escape the feeling that he is cursed, haunted by the ghosts of those soldiers he let down. Inevitably, the sea monster he spared returns, bigger, more powerful, and threatening the mainland. Of course, it is Godzilla, but to Shikishima it is destiny itself, come to collect on his earlier lapses of duty, with interest.

In the most harrowing sequence, he watches Godzilla destroy the new buildings in the Ginza district of Tokyo, undoing the progress achieved since the war’s end, and helpless to rescue the one person who has become most precious to him. Godzilla has always had greater resonance for Japanese audiences and creators than he has for Americans, and this film is more politically potent than many installments of the series, but in the moment in which Shikishima watches everything swept away—horrible enough, but made moreso by the knowledge that he could have prevented it—Godzilla Minus One strikes me as a movie about climate change and the numerous disasters that have hammered Japan because of it as much as a statement about war (although of course it is that, too). Godzilla Minus One is an epic, in its own way like Oppenheimer focused on the question, “What can one man do? What does he owe the world, and what himself?” The comparison of the two films, centered on the same time period, the same pivotal moment, reveals differences in both national outlook and artistic temperament. Both films are riveting, grandiose cinematic spectacles and neither presents easy answers.

Thanks for reading! Let me know if I missed any of your favorites from last year, and have a great 2024!