The studios that produced serials were nothing if not parsimonious: considering the ways in which stock footage, costumes, and other production elements were reused, it is not surprising that the films themselves would be repackaged and rereleased as many times as were profitable. During the heyday of the serial format, a popular serial could be rereleased in its entirety after a few years (there were no options for viewers to see them in any other way, of course, and since most were aimed at youngsters, a new audience would arise over time).

Serials were also frequently edited down to feature length (anywhere from sixty to a hundred minutes), either released simultaneously with the serial or later rereleased as “B” pictures. The arrival of television introduced a new market for “featurized” serials, as well. (As an example, in 1966, Republic made a number of its films available to television, both complete serials and several cut down to one hundred minutes.) Sometimes, but not always, these shortened serials reappeared under new titles: Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars was released simultaneously with the feature-length Mars Attacks the World, its title chosen to exploit the notoriety of Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast; Undersea Kingdom surfaced on television as Sharad of Atlantis; and so on.

Since I began exploring the serials last summer, I’ve been curious about these feature-length cuts: how do they differ from the serialized originals, and how effective are they at conveying the story and its thrills? There is no one answer: even a cursory survey reveals differing approaches to editing and marketing, and the context of production and the studio’s goals can have a big impact on the final product. In theory, one could cut the titles and credits and the redundant material from the cliffhangers and have a perfectly serviceable movie. In reality, the end product would still be too long for what was considered “feature length” in the mid-twentieth century and the pacing might prove unsatisfying for one sitting. From what I can tell, most cut-down serials come in somewhere between an hour and an hour and a half. (Editing down a serial into a more modern feature length would undoubtedly be an interesting project for a film student or anyone who wants to learn more about the pacing and construction of these films. Indeed, YouTube searches reveal a range of cleaned-up and “restored” versions; how far these restoration efforts extend into actual recutting is a question I haven’t explored in depth.)

For purposes of comparison I sought out a few “featurized” versions of serials I have already reviewed for this series. An approach that I would assume is typical is seen in the shortened cut of Shadow of Chinatown: at a brisk 69 minutes, the feature zips through the major events of the serial. Much of the “Oriental” color is done away with, as are scenes that have Martin Andrews’ manservant Willy Fu briefly kidnapped, and a car chase between Los Angeles and San Francisco. What is mostly eliminated is repetitive or slow-moving, however; everything that’s left is worthwhile, and more importantly the story makes sense. Willy gets in a few of his pseudo-Confusion aphorisms, and Bela Lugosi still has enough screen time to justify his top billing.

Interestingly, however, the reduction of the action to its most exciting elements makes reporter Joan Whiting a more obvious (and sympathetic) lead character than the mansplaining Andrews, at least for a while. Also, the ending cuts off one final twist in which Lugosi’s character comes back from an apparent death to strike at Andrews: this time, he gets his comeuppance the first time. There are a few other small changes, such as the addition of musical underscore to scenes that were without accompaniment in the serial, at least the version I watched; that seems to be pretty standard practice, a way of covering the seams and updating the production. Although I enjoyed the full serial of Shadow of Chinatown, I would consider the feature version an adequate substitute for an interested viewer.

By contrast, the feature-length cut of The Phantom Empire feels rushed. Admittedly, its story is complex, with Gene Autry and his Radio Ranch friends pitted against both an unscrupulous radium-hunting scientist and denizens of Murania, the hidden realm located 25,000 feet beneath the surface. Much of what I appreciate in this serial is around the edges, however: those small atmospheric moments or character beats that make it unique. As a feature, The Phantom Empire is still very distinctive. Autry’s musical numbers, integral to the plot (he must broadcast every day or else lose his radio contract, and thus the ranch), are still there, as are Frankie and Betsy Baxter’s DIY electronics lab and their club, the Thunder Riders. Missing, however, are those scenes in which Murania’s Queen Tika spies on the surface world through her television, seething with disdain, as well as a similar scene in which she shows Autry the realities of poverty and war on the surface. Gone also are most of Autry’s fight scenes and a sequence in which, near death, he mumbles in the backwards “language of the dead” before being revived by the miracle of radium. The murder of Tom Baxter is glossed over even more than in the serial, without much time given for it to sink in.

The biggest loss is the erasure of Queen Tika’s motivation for keeping Murania hidden and, ultimately, deciding to stay with her kingdom during its destruction instead of fleeing to the upper world with Autry. Speechifying is something sci-fi fans often tolerate rather than enjoy, and it’s usually the easiest thing to cut when editing for length, but in this case reducing Tika’s presence drains the serial of much of its personality, turning her into another cardboard villain. If most viewers between the 1950s and 1990s were only able to see the feature-length cut, it’s not surprising that The Phantom Empire is appreciated only by aficionados: without the atmosphere and dramatic build-up found in the full version, it comes off as a diverting novelty in the mold of Undersea Kingdom.

The New Adventures of Tarzan was actually edited into two feature films. The first, also called The New Adventures of Tarzan, is a longer version of the first two chapters of the serial, in which Tarzan joins the Guatemalan expedition of Major Martling in order to find his friend, the downed pilot D’Arnot, who is trapped in the same “lost city” in which Martling hopes to find a legendary idol, the Green Goddess. Also hunting for the idol is Raglan, a rival explorer working for a foreign company that wants the explosive formula hidden inside the idol. Although two chapters doesn’t sound like very much, the first chapter of the serial is an unusual forty minutes long, so stretching the film to seventy minutes isn’t as odd as it sounds.

(Also worth noting: while the feature’s release date is given as 1935, a release simultaneous with the serial, the version I watched is obviously a later rerelease, as the leading man is listed as Bruce Bennett; Brix changed his name to Bennett in 1939, a change that coincided with a transition into more prestigious Hollywood fare such as Sahara, Dark Passage, and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. The music that accompanies these updated credits also sounds like something from the 1940s.)

As I mentioned in my review of the serial, I had trouble following the first chapter’s setup, as the sound was patchy and some of the dialogue was hard to understand. The feature version clarifies things a great deal by including extra scenes of dialogue and improving the sound. Some of the dialogue is obviously dubbed, and the voice coming from Tarzan’s mouth doesn’t sound like Herman Brix; I wonder if this version was the cause of John Taliafero’s complaints about Brix sounding like a “school master:” it’s both higher and fussier than Brix’s normal speaking voice, and it doesn’t sound like anyone’s idea of the lord of the jungle. As for the rest of the dubbing, it at least helps the story make sense, and there are also added background music and sound effects that give the film a more complete, modern atmosphere.

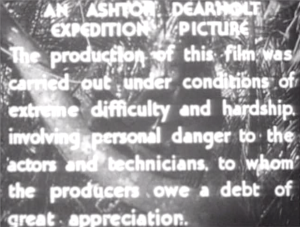

Even so, the film begins with an apology for the sound quality, recorded under difficult conditions, and begs for the indulgence of the audience. It’s hard to imagine any modern film making such a plea, unless it were a documentary. Taliafero mentions that the Ashton Dearholt expedition that filmed The New Adventures in Central America ended up with enough footage for both a serial and a feature film, and sure enough there is a great deal of footage that doesn’t appear in the serial. Much of it is atmospheric footage of wild animals, natives, and the exotic country, and while it is impressive on its own, its inclusion in the finished film often smacks of padding, giving the film the air of a travelogue punctuated by a few scenes of action. (Particularly shameless is a flashback to D’Arnot’s plane crash that includes almost five minutes of aerial footage of animals before the actual crack-up.)

Some of the events from the serial are rearranged slightly (and obviously the cliffhangers from the serial are simply played out as action scenes without interruption), but the biggest change is at the end: in the serial, Raglan is able to steal the idol from the lost city and make away with it, with Martling and Tarzan on his trail. In the feature, Tarzan recovers the idol from Raglan almost immediately after he steals it and Martling is able to open it right there, finding the jewels inside. A happy ending for all!

Of course, Raglan gets away, and his (as well as the lost city cultists’) attempts to take back the idol are the main thread of Tarzan and the Green Goddess, the 1938 feature that includes the rest of the serial. In this film, the raw material of The New Adventures undergoes a more interesting transformation. The last chapter of the serial takes place at Lord Greystoke’s British estate, where he is holding a Gypsy-themed costume party; some of his guests ask him to recount his recent adventure in Guatemala, and he does so in flashback, turning the last episode into a belated “economy chapter.” Green Goddess puts this frame device around the entire film, which takes up the action following the escape from the lost city. The movie barely reaches an hour in length, and without the padding found in the first feature the plot moves at a breakneck pace (although it still finds room for a scene in which Martling’s valet George chases a monkey who has stolen his yo-yo). Despite being edited together with more sophistication than the 1935 releases, I’m glad I had seen the whole serial before watching this, for the sake of clarity.

Finally, there is the issue of availability. After long years of being hard to find, even for collectors (Harmon and Glut’s 1972 The Great Movie Serials, a book I have found an invaluable resource for this series, was partially based on memories of serials sometimes seen years before, and occasionally the distance shows in distorted or jumbled details), home video made it possible for many serials to be seen as they were originally released, and websites like YouTube and the Internet Archive have made it even easier for anyone with an internet connection to watch these films. In the case of feature-length cuts, the internet is frequently the only choice, as even high-quality restorations for home video don’t usually see fit to include them (I watched the feature versions of both Shadow of Chinatown and The Phantom Empire on YouTube).

Having said that, since many serials and their feature cuts are in the public domain or can be considered “orphan works,” I have found that they also turn up on cheap movie-compilation DVDs. Both of the Tarzan features I have discussed here are included on a Mill Creek collection entitled Wrath of the Sword: 20 Legendary Movies, which includes several Tarzan movies from the 1930s, a bunch of sword-and-sandal movies from the ’50s and ’60s, and (for some reason) one random Christopher Lambert movie from 2005. There’s nothing in the packaging of Wrath of the Sword that would indicate that the two Tarzan movies are related sequentially or derived from the same serial, but that’s part of the fun of this sort of quantity-over-quality package: you never really know what you’re going to get, and you have the opportunity to make discoveries and draw your own conclusions.

Next week I’ll be back with regular serial coverage as I examine The Green Hornet.