Yes, that’s right. Ten years ago this month, I launched Medleyana, and it’s still going—well, maybe not going strong, but it’s going. This year in particular has been pretty fallow, and I couldn’t blame anyone for thinking that I’d abandoned it for good. All I can say is that I’ve been occupied with work and other personal projects that have taken up my time, but now I’m back. The approach of the spooky season in October usually gives me something to write about, so at a minimum you can expect a Halloween wrap-up at the end of the month.

But for now, I feel justified in taking a small victory lap and indulging in something I don’t do very often: repackaging old articles in new lists. I’ve gone through my posts and chosen ten of my favorites, one from each year of Medleyana’s existence (counting a year as beginning in September—you can take the academic out of the academy, but . . . ). Some of these are articles I still post links to when I feel compelled to summarize my viewpoint on a particular subject, and others are deep dives into my own personal interests. If you’ve been following me since the beginning, thank you, and I hope these are pleasant reminders of where we came from. If you’re new to Medleyana, consider this a sampler, all of them examples of what I mean by the blog’s slogan, “In praise of the eclectic.”

Everybody’s Looking for Some Action (November 2013)

When I began Medleyana, I started out by writing connected series and multi-subject articles in which I tried to get out ideas that had long occupied me, but even in the first year I started to get the hang of writing focused essays on single subjects. Since this article on collecting comic books was posted, I’ve become more serious about building and organizing my collection, and I ended up writing about comics a fair amount. But I’m still not planning on funding my retirement with them.

In the Hall of Mirrors with Captain Carrot and His Amazing Zoo Crew (October 2014)

This one combines several themes that I returned to over the years: review, commentary, and a bit of history as I look at an idiosyncratic “funny animal” comic book series.

The Short Horrors of Robert E. Howard (October 2015)

The history of the pulps, both the magazines and the writers, is another subject I delved into quite a bit, and in this essay I investigated the contents of several horror-focused short story collections by the creator of Conan the Barbarian.

Remake, Revisited (January 2017)

I saw Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny earlier this summer, and I enjoyed it. The de-aging technology that made Harrison Ford look younger for a prologue set during World War II has continued to improve, but I couldn’t help wondering: if this technology had been available when they made Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade in 1989, would we have had the wonderful prologue with River Phoenix as young Indy?

Written in response to Rogue One, with its CGI-generated Peter Cushing and de-aged Carrie Fisher, this article has only become more relevant since. As of this writing, so-called “AI” threatens to upend every creative industry, and Hollywood writers and actors are striking, in part against the prospect of being replaced or devalued by chatbots and infinitely pliable computer simulations. The increased churn of low-quality streaming content and never-ending franchise service has reached a point of unsustainability, and audiences are already beginning to turn away. I stand by the assertion made in this article that CGI tools can be used responsibly, but they are just that, tools: algorithms don’t have original ideas, they don’t have desires or viewpoints to express, and they aren’t going to live up to producers’ fantasies of steady, guaranteed revenue forever.

Kamandi Challenge no. 9 (September 2017)

My interest in Jack Kirby’s science fiction comic Kamandi is another subject I’ve written about several times, and in 2017, Kirby’s centenary year, I posted issue-by-issue reviews of Kamandi Challenge, a tribute series in which rotating teams of artists and writers took on the character and his world, setting up a cliffhanger at the end of each issue for the next team to unravel. Issue no. 9 was a fascinating standalone story that explored some of Kamandi’s psychology and allowed me to express my thoughts on Jack Kirby’s qualities as a storyteller.

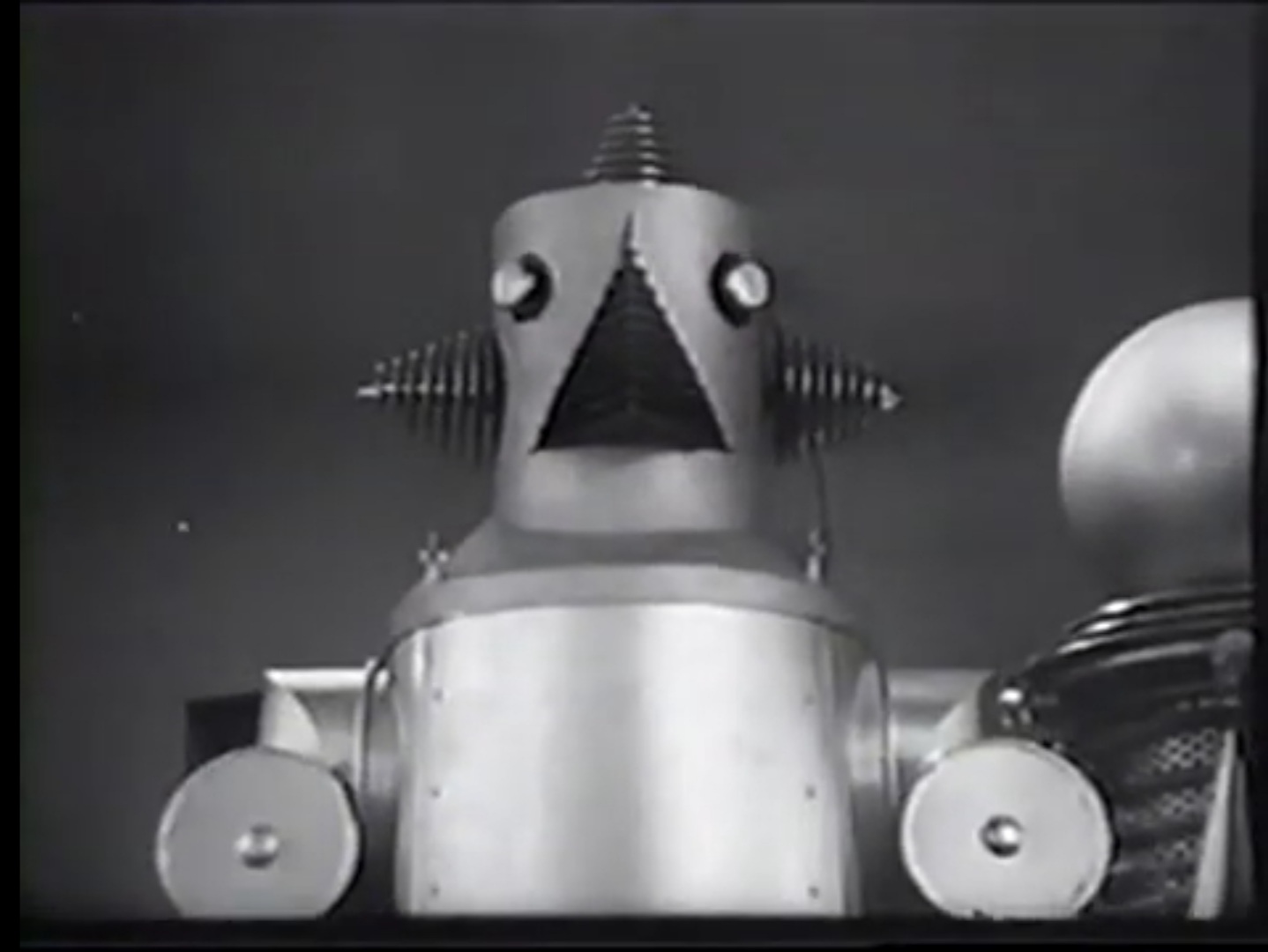

Fates Worse Than Death: Secret Service in Darkest Africa (September 2019)

A large number of my posts on Medleyana have been reviews of serials from the silent film era up to the 1950s, when the formula of narrative by weekly installment migrated to television. Although I was mostly interested in exploring the two-fisted adventure aesthetic (shared by the pulp magazines and Golden Age comics) at first, I learned a lot about plotting and setting up story conflicts with stakes, and going through each serial to take screenshots for illustrative purposes ended up being an education in composition and blocking. This review is typical, and if you enjoy it, there’s much more where it came from.

Color Out of Space: Horror Comes Home (January 2020)

Combining my interests in film, the pulps, and horror, this review gets at some of the challenges we face when we attempt to “separate the art from the artist.”

Thoughts on Electric Light Orchestra’s “Twilight” (March 2021)

When I began Medleyana, I thought I would primarily write about music. This article is a bit of a throwback in that it combines a couple of topics and bounces them off each other, but it’s also a good indicator of my increased interest in anime over the last decade as I examine the seminal fan film Daicon IV and its legacy.

Revenge of the Ninjanuary: Ninja Scroll (January 2022)

Speaking of anime, this review is an example of that interest as well as representing my growing interest in martial arts and ninja media.

Halloween on a Monday: Spooktober 2022 (October 2022)

From the beginning, I’ve celebrated Halloween on the blog, culminating with a month’s-end list of spooky movies I watched and other activities I participated in. Last year’s wrap-up included meditations on the passage of time, mortality, and the reasons we like to scare ourselves, a theme that Medleyana ended up exploring much more than I expected when I began writing. I had just turned 40 when I started this blog, and now I’m 50. (It’s been a year since my wife was treated for the cancer I mention in this post, and she’s doing well, thanks for asking.) The last decade has been one of exploring interests that had been set aside because of school and work, including many new discoveries that hadn’t even been on my radar before I started writing. (It’s a good thing I had such an open-ended format from the beginning.) If I haven’t accomplished everything I set out to do, I’ve had other opportunities and made new friends that I didn’t expect. The very landscape of the internet has changed since I started—it’s mostly worse—but I’m proud of what I’ve created. It’s been a journey. Thank you for coming along with me.