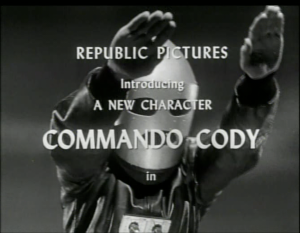

Although movie studios adapted many popular characters from the comics, radio, and literature for serials, they eventually grew tired of paying license fees and squabbling over creative control and came up with thinly-disguised copies of licensed characters, changing (for example) the Phantom to “Captain Africa” or Zorro to “Don Daredevil.” This allowed filmmakers to reuse footage from earlier productions without paying to license the characters again. Studios also created a few original characters, such as Rocket Man/Commando Cody.

Zorro’s Black Whip, however, is an unusual case, a seemingly superfluous license: aside from the title, the lead character, the “Black Whip,” is never referred to as Zorro at all, and only superficially resembles Johnston McCulley’s masked avenger. Zorro’s Black Whip doesn’t even take place in Mexico or the Southwest: the story is set in the Idaho Territory in 1889, just before elections to determine Idaho’s statehood. However, the use of Zorro’s name in the title undoubtedly sold tickets, and the film’s reputation for being “the female Zorro” has given it a sort of immortality.

So Zorro’s Black Whip, despite its title, is a fairly straightforward Western with a masked hero. It begins with a title card describing rampant lawlessness on the eve of statehood elections:

Law-abiding citizens called for a vote to bring their territory into the Union. But sinister forces, opposed to the coming of law and order, instigated a reign of terror against the lives and property of all who favored statehood.

After a montage of masked horsemen attacking wagon trains, burning settlements, and robbing a bank, the scene changes to a meeting of the “citizens’ committee,” including pro-statehood newspaper editor Randolph Meredith, at the offices of stagecoach operator Dan Hammond. A federal commissioner is arriving in the territory in response to the bank robbery, driven by Meredith’s sister Barbara; he’ll take charge of law and order in the area until the elections.

After the meeting, Hammond confers with his henchmen, Baxter and Harris: it is Hammond who is behind the outlaws’ depredations, and he’ll stop at nothing to prevent statehood from wrecking his plans to control the territory. (Yes, this is the same motive as Kraft’s in Fighting with Kit Carson.) Hammond sends his goons to eliminate the commissioner and capture Barbara in order to force her brother to stop pushing for statehood in his newspaper.

A chance meeting with Vic Gordon, a railroad surveyor, gives Barbara and the commissioner a fighting chance, and when the Black Whip rides in to assist, Baxter and Harris are outmatched and retreat. It’s too late for the commissioner, however, and before he dies of his wounds he reveals that Gordon is an undercover agent working for him, deputizing Barbara to help Gordon “stamp out these evils [and] bring Idaho into the Union.”

The Black Whip, also injured, returns to his lair behind a waterfall; as he unmasks before dying, we see that it is Randolph Meredith, and the secret entrance connects to his and Barbara’s ranch house. When she returns home, looking for him, she finds his body and learns the truth. From then on, she wears the costume and takes on the responsibilities of the Black Whip, as well as the newspaper, with the aid of Vic Gordon.

There are quite a few complications before Hammond is eventually brought to justice: Gordon is briefly framed for stealing reward money he had collected, and is almost lynched by an angry mob; Barbara is captured with the intention of forcing her to reveal the Black Whip’s identity; Gordon learns the truth and puts on the Black Whip costume to avert suspicion that Barbara is the masked vigilante.

Throughout, Barbara uses the newspaper to pass information along and provide handy visual summaries for the audience: HERALD EDITOR MURDERED; $10,000 REWARD; BIG GOLD STRIKE AT HARPER’S CREEK, etc. At the same time, Hammond secretly uses his position as a businessman and member of the citizens’ committee to shape public opinion and stymie attempts to curb the outlaws. It’s a surprisingly urban approach to the Western, with gangsters using six-shooters instead of tommy guns and getting away on horseback instead of in black sedans.

Also contributing to the contemporary feel, I was struck by the fact that everyone has a telephone. At first this seemed anachronistic to me, but reliable sources inform me that the first commercial telephone service in Idaho was established in 1883, so I can now claim the entire four hours of Zorro’s Black Whip as “educational viewing.” In other ways it is a typical Hollywood production: there are no Native Americans or people of color at all, sparing us the usual problematic racial depictions but also whitewashing away any real history. (I know, expecting “real history” was probably too much, but the telephone thing got my hopes up.) In fact, probably the most jarring element from a modern perspective is typesetter “Ten Point” Jackson’s addiction to patent medicines (like a “jitters tonic” helpfully labeled “90% alcohol”), played as comic relief.

The performances are uniformly excellent and, in combination with the writing (credited to four people: Basil Dickey, Jesse Duffy, Grant Nelson, and Joseph Poland), give the characters a lived-in quality. As Vic Gordon, George J. Lewis is the first billed, but Linda Stirling as Barbara/the Black Whip should really be considered the star. (As in most serials, no one person is responsible for moving the entire plot forward, but come on, she’s the title character and was the focus in promotional materials.) Lewis comes off as somewhat glib, flashing a movie-star smile at the end of most of his scenes, whether appropriate to the moment or not.

Who knows—maybe he really had the hots for Stirling, and who could blame him? Beautiful and self-possessed, Stirling is considered one of the “serial queens” of the era, having previously appeared in The Tiger Woman, a jungle adventure; she here shows both an ability to act and carry a stunt-heavy action picture, riding, shooting, and dispatching bad guys with the long whip from which her alter ego takes its name. (Unlike Pearl White, however, she didn’t do all her own stunts.) On the villains’ side, Francis McDonald gives a wiry intensity to Hammond, and Hal Taliaferro is physically imposing and laconic in the manner of John Wayne as Hammond’s chief henchman Baxter.

From a technical standpoint, this is one of the most tightly assembled serials I’ve watched so far. Directors Spencer Gordon Bennet and Wallace A. Grissell frame the action clearly and keep the pace up, aided by the cast’s game performances. Famed Western stunt coordinator Yakima Canutt serves as second unit director, contributing his expertise to the numerous horseback gunfights, chases and careening wagons that fill the running time. Also present are Tom Steele and Dale Van Sickel, who would typically play a few henchmen or other bit parts while coordinating fistfights and other stunts behind the scenes. Finally, Theodore Lydecker is in charge of special effects, and his miniature work is recognizable in several shots, such as a cabin being flattened by a rockslide (according to imdb, Theodore’s brother Howard did uncredited work as well, which would make sense: they usually worked as a team). Zorro’s Black Whip is a showcase for some of Republic’s production talent at a high point of quality.

The fight scenes are especially prominent and well executed, and Republic must have spent half its budget for this picture on breakaway furniture. Several locations are demolished by fights (including the newspaper office, the stagecoach office, an abandoned mine tunnel, and several barns and shacks), the fighters throwing each other over and through objects, and the furniture and any loose items being turned into impromptu clubs or missiles. When a fight breaks out in Barbara’s sitting room, with its flimsy knick-knack shelves and parlor furniture, it’s as thoroughly trashed as in any juvenile delinquent movie of the 1950s. In another fight scene, everything in the room, up to and including a cast-iron stove, comes crashing down during the brawl. It’s a credit to the choreography that these fights never become dull or repetitive.

In The Great Movie Serials, Jim Harmon and Donald F. Glut highlight the contradictions inherent in the serial heroine: do audiences want to see an avenging she-devil whipping her male oppressors, or a bound victim awaiting rescue? It’s the same question posed by The Perils of Pauline in an updated package.

Harmon and Glut even go so far as to draw a connection between Stirling’s tight costume and “man-abusing actions” and “certain forms of underground erotica” (the book was written in 1972). I wonder, however, if through hindsight they were overstating the film’s effect on their younger selves. It’s possible to read the Black Whip as a predecessor of Russ Meyer’s “supervixens”—there’s definitely a lot of whipping in this film, and one can imagine it charging the imagination of some young Russ Meyers in the audience—but Linda Stirling is no Tura Satana, and Zorro’s Black Whip, while entertaining in its own right, will never be mistaken for Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!

What I Watched: Zorro’s Black Whip (Republic, 1944)

Where I Watched It: A Roan Group Archival Entertainment DVD; it’s also available to watch on YouTube.

No. of Chapters: 12

Best Chapter Title: “Take Off That Mask!” (Chapter Five)

Best Cliffhanger: Fittingly for a serial that places such a premium on action, there are many excellent cliffhangers in Zorro’s Black Whip. There are several falls off of cliffs, of course, in and out of speeding wagons; there are explosions, including a burning barrel of coal oil in a dead-end mine tunnel. There’s quite a bit of violence which is grisly in its implication, if not very graphic in its depiction (and lest you think that whip is just for show, the Black Whip totally whips a guy backwards off the edge of a cliff at one point). I think my favorite cliffhanger is in Chapter Ten, “Fangs of Doom,” the title of which leads me to expect a rattlesnake (or maybe . . . a vampire?). As it happens, during a fight in a barn, in which a variety of riding tack and farm implements are thrown around, the Black Whip is knocked out, and Baxter attempts to finish her off with a pitchfork(!), thrusting it downward with a sickening crunch.

Annie Wilkes Award for Blatant Cheat: But wait! At the last minute, Gordon throws a saddle over the Black Whip’s torso, so the sickening crunch is the sound of the pitchfork driving into the hard leather. Okay, it’s not a cheat, but come on . . . a saddle?

Sample Dialogue: “The Black Whip’s got to be a man! He’s out-shot us, out-rode us, and out-fought us, stopped us at every turn!” –Baxter to Hammond, Chapter Nine (“Avalanche”)

What Others Have Said: “What still remains a mystery to viewers of Zorro’s Black Whip is that those crooks could wrestle around the barn so many times with the avenger without somehow discovering the true sex of the ‘masked man.’” –Harmon and Glut, The Great Movie Serials

What’s Next: Next week I plan to publish a special serial-related article, and then in two weeks I’ll be back with my impression of Gang Busters, the final installment of Fates Worse Than Death until next summer. See you then!