Deep in the rugged mountains between Siam and Burma, the Malcolm Archaeological Expedition has reached its destination, the Valley of the Tombs, in the shadow of Mount Scorpio. Despite warnings from local tribesmen that the Valley is taboo, John Malcolm is determined to open the sealed inner tomb, unlocking the “lost secret of the Scorpion Dynasty.” The expedition’s translator, native Tal Chotali, reads an inscription: “Let what reposes behind this stone remain hidden from the eyes of mankind for all time.” A terrible curse is about to be unleashed! The youngest member of the expedition, Billy Batson, wants no part of tomb raiding, so he leaves the room. The expedition members open the tomb without him, uncovering a fabulous scorpion-shaped idol holding a series of lenses in its claws. As soon as they move the lenses to line up with a beam of sunlight, it releases a burst of energy that shakes the earth and traps the men inside the chamber.

Meanwhile, Billy wanders into another chamber of the tomb; to his shock, a previously sealed tomb opens, and an impossibly old man steps out! Because he did not desecrate the tomb, Billy Batson is to be given the mantle of Captain Marvel to protect the innocent from the power the scorpion idol is about to unleash. Captain Marvel combines the virtues of six mythological figures: the wisdom of Solomon, the strength of Hercules, the stamina of Atlas, the power of Zeus, the courage of Achilles, and the speed of Mercury. The initials of these six names combine into the magic word “Shazam” (also the name of the wizard), with which Billy transforms into Captain Marvel and back again. He is put to the test immediately, becoming Captain Marvel to rescue the explorers who have been trapped in the cave-in.

Once everyone is outside and reunited (and Billy is himself again), the members of the expedition learn just how powerful the scorpion idol is: sunlight focused through its lenses in the right order can turn ordinary rocks into gold, or generate an incredibly powerful ray (later it is referred to specifically as a “solar atom smasher”). Recognizing that the idol is too powerful for one man to control, and that it would be a target for theft, the members of the expedition divide the lenses between themselves, each man to guard and keep one safe; the power of the idol will never be used unless it is by the assent of the entire group.

That night, the expedition’s stockade is attacked by native tribesmen on horseback, led by a hooded mastermind who calls himself “the Scorpion.” The Scorpion claims to speak for the tribe’s god, and his goal is to reunite the idol with its lenses and use its power for conquest. During the assault, one of the expedition members is killed and the idol stolen. Billy Batson goes into action as Captain Marvel once again, routing the attackers, but unbeknownst to him the tribesmen have also planted dynamite beneath the bridge leading from the encampment: will the expedition’s retreat be thwarted by the explosives, or will Captain Marvel save the day? All of this occurs in the first (double length) chapter of the classic 1941 Republic serial, Adventures of Captain Marvel!

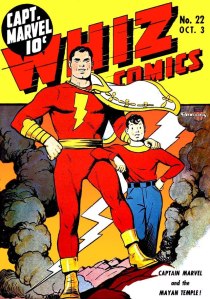

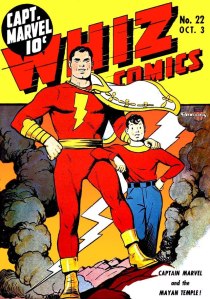

Captain Marvel, co-created by Fawcett writer Bill Parker and artist C. C. Beck, was one of many superheroes who appeared in the wake of Superman’s success, and among the most popular, even outselling Superman himself during his heyday. Much has been written elsewhere about the lawsuit National (later DC) filed against Fawcett alleging copyright infringement, and the long legal battle that followed (I have touched on it here). Ultimately, Fawcett ceased publishing Captain Marvel comics in 1953, exhausted by the legal battle and faced with declining sales, and the hero was licensed by DC in the 1970s as “Shazam” (the name “Captain Marvel” having been claimed by Marvel Comics in the interim) and bought outright in 1980; a live-action Shazam movie is scheduled to be released in 2019 as part of DC’s ongoing film universe.

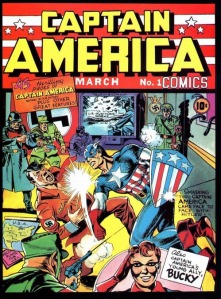

As of 1941, however, Captain Marvel was riding high, and became the first comic book superhero to make the leap to the big screen (ironically enough, Republic tried to make a deal to adapt Superman first, but it ultimately fell through and Superman first appeared in theaters in a series of animated cartoons; the hero would be a latecomer to the film serials, not appearing in live action until 1948). In reading about Adventures of Captain Marvel (no “the”), I was struck by the way it follows typical serial procedure in adapting its source material, tying the hero’s origin to its villain and putting the scorpion idol and its lenses at the center of the story. I assumed that it was another case of Republic adapting the source material “in name only” as they would later do with Captain America, so it was a pleasant surprise to see how faithful to the comics the serial was in many other respects.

The biggest difference is the serial’s connection of Shazam to the Scorpion tomb, but otherwise Captain Marvel’s origin in the comics was similar: in Whiz Comics no. 2, Billy Batson, an orphaned newsboy (an actual boy, unlike the boyish young adult Billy played by Frank Coghlan, Jr. in the serial) was led to the wizard Shazam in an abandoned subway tunnel, and he was given the assignment to protect humanity as an ongoing mission rather than a specific task. But the magic word, the mythological connections, and Captain Marvel’s powers are all there. What’s more, the serial Captain Marvel (Tom Tyler) looks a great deal more like his comic book counterpart than the serial versions of Batman or Captain America do, wearing a good-looking uniform and even appearing to fly through the air.

All of the effects in this serial, by Republic’s stalwart team of Howard and Theodore Lydecker, are top-notch, including those convincing flight sequences and many of the miniatures (sorry, “scale models”) for which the Lydeckers are famous. The illusion of flight was achieved by a variety of techniques, including a papier-maché dummy strung on a wire for the long shots, cut together with shots of Tom Tyler (or his double, legendary stuntman Dave Sharpe) leaping into the air from a hidden trampoline or coming in for a landing in slow motion. (Sharpe was also responsible for Captain Marvel’s athletic moves during fight scenes, including an amazing, back-flipping kick in the first chapter.) The wires are visible in some of the shots of Tyler suspended in mid-air, clouds whizzing by, but they are easy to overlook if you are as fascinated by practical effects as I am, or if, like the young and young-at-heart audiences to which the serial is directed, you’re so swept up in the story that you don’t even notice them. The flight effects look good “for their time,” but even now one has to appreciate the ambition it took to attempt them in live action (recall that the same effects in the later Superman serials were achieved with animation). And like the best cinematic fantasy, the story, in its surging forward motion, demands belief as the price of admission where scenes viewed in isolation might provoke skepticism.

Another contrast with the comics is its tone. Captain Marvel’s adventures in the comics (mostly written by pulpsmith Otto Binder) were fantastic exercises in whimsy, often to the point of silliness, held together with fairy-tale logic or wordplay. Captain Marvel traveled to exotic foreign countries and even other planets; he fought mad scientists and magicians (his most famous recurring nemesis, Dr. Sivana, was the former); he added the growing “Marvel family” to his supporting cast, including Mary Marvel, Captain Marvel, Jr., and even “Hoppy, the Marvel Bunny”; he even made friends with a talking tiger who became his roommate! And all of this is balanced with the fantasy of being a boy but living independently (after being a newsboy, Billy Batson held down a job as an announcer for radio station WHIZ). Binder’s fanciful stories were a perfect match for Beck’s clean, simple drawing style, and the nuttiness of the plots is comparable to the mischief William Marston’s Wonder Woman would get up to over at National, but without the marked gender play (in fact, Captain Marvel is a notably prepubescent fantasy, as the hero would become nervous and shy around women, resisting the overtures of Dr. Sivana’s daughter Beautia). As Matt Singer notes (in his essay accompanying the Kino Lorber Blu-ray), the brilliance of the Billy/Captain Marvel divide was that it “fused hero and sidekick into a single figure.”

By contrast, the serial’s tone is serious, if not downright grim. Gone are Dr. Sivana’s whimsical schemes (in fact, gone is Dr. Sivana), gone are the talking animals and such fanciful locations as the “Rock of Eternity” (the heaven in which the late wizard Shazam now dwells in spirit form). Instead of being matched against other superpowered beings, Captain Marvel wastes an army of generic fedora-wearing henchmen (and I do mean wastes: writer Tom Weaver points out that Captain Marvel kills more people than the villain in this serial, throwing them off buildings or turning their own guns against them). Animation historian Jerry Beck rightly compares Captain Marvel in his scenes to a Universal monster, breaking down doors and pressing forward in the face of gunfire that bounces off of him harmlessly (at least the thugs don’t try the last-ditch effort of throwing their empty guns at him, as seen so often in the Superman TV series), his smile “more like an animal bearing its teeth.” Once the Scorpion’s men know what they’re up against, their reaction is one of sheer terror.

Other ingredients that contribute to the serious tone are standard serial fare: the archaeological expedition, as well as the curse that followed the opening of the tomb (inspired by the supposed curse of King Tut’s tomb), were common features of serials in the 1930s (and a prime inspiration for the Indiana Jones series, of course); the serial begins and ends in the Valley of the Tombs (propped up with footage from earlier movies), even though the rest of the action takes place in America. Of course the Scorpion himself, the hooded figure of evil derived from the Grand Guignol theater and the mystery novels of Edgar Wallace, is a key element of the serial vocabulary, as is the Scorpion’s methodical elimination of the expedition members, collecting their lenses one by one, even as he himself is secretly one of their number. Only in the last chapter is the Scorpion’s true identity revealed; in fact, his lines are spoken throughout by uncredited actor Gerald Mohr, just to make sure we don’t guess prematurely. (The need to avoid spoiling the surprise leads to some amusing decisions: in one chapter, the members of the expedition abandon a sinking ship and make their way to land by rope; Betty, the story’s lone female character, goes to her cabin to retrieve something, only to be knocked unconscious by the Scorpion–in costume–and left to sink with the ship. It should be obvious that the Scorpion has no reason to hide his identity from one he believes will soon be dead, and that sneaking around in costume increases the risk of being caught, but the costume is for the benefit of the audience, not the Scorpion’s victims.) Even at the end, when there are only two suspects left, and one shoots the other, revealing his true identity, the scene is filmed in shadow, the voices disguised, so as to preserve the delicious moment when Captain Marvel can pull off the captive Scorpion’s mask himself for all to see.

Still, the mood is not too heavy, leavened by swiftly-moving action and dialogue and a rapid-fire change of scenes. Coghlan’s Billy, as well as his youthful friends Whitey (William Benedict) and Betty (Louise Currie), are a big part of that, striking a “gee whiz” attitude midway between the kid-oriented comics and the deadly serious business of the Scorpion. Adventures of Captain Marvel is frequently held up as one of the best serials of all time, and it is easy to see why: all of the technical resources of Republic are working at their peak, from the Lydecker brothers’ fantastic effects to the direction of serial superteam William Witney and John English and the stirring music by Cy Feuer. A solid script provides plenty of opportunities for the cast (including, in addition to the leads, such frequently-seen character actors as John Davidson, who plays the enigmatic Tal Chotali) to develop their characters (within a framework primarily defined by action and intrigue, of course).

Furthermore, while I have sometimes expressed boredom at the formulaic nature of Republic’s later serials in comparison to the wild and weird serials of the 1930s, at the sense that they run too smoothly, Captain Marvel strikes a very satisfying balance between technical precision and characters who still act human, who are capable of surprising. (It probably helps that Republic was not yet at the point of recycling entire cliffhangers, so the situations flow organically from the story.) Betty is a good example of this: when taken captive by the Scorpion’s men, several times she sees opportunities to attempt escape and takes them rather than waiting around for Captain Marvel, even desperately grabbing the Scorpion’s own gun and attempting to shoot him. (This leads to a sequence in which Billy believes the Scorpion has an injured hand and tries to flush him out by gathering the expedition members together.) In addition to lending an unpredictable realism to the proceedings, Betty’s actions (and similar unexpected actions by other characters) drive the story forward: neither the Scorpion nor Captain Marvel have everything their way all the time.

Finally, I have occasionally noticed a generational divide in how the fanciful comic books of the Golden Age and its related media are received, and the commentary on the Blu-ray provides an illuminating example: Tom Weaver, a self-described Baby Boomer, mentions going back to read some of the original Captain Marvel comics (for the first time, as an adult) and his disgust at their silliness is palpable. “The comic book is so juvenile,” he reports, “that I can’t imagine who read it and thought ‘This might be good for a Republic serial.'” He complains that Otto Binder’s Captain cracks corny jokes while fighting, as if that weren’t something common to almost every superhero before the 1980s. For him, and for many viewers like him, the seriousness of the serial is a step up, a necessary refinement of material that is otherwise not worthy of consideration. By contrast, younger viewers and readers, especially those who may have already encountered Captain Marvel in reprints or through one of his post-1970s television iterations at a young age (and that may be the real key, the “Golden Age” being twelve years old and all that), readily accept the childlike fantasy inherent in the character. (On the Blu-ray it is the hosts of the podcast Comic Geek Speak, children of the 1970s and ’80s by the sound of it, who represent this point of view, but I have encountered it among comics fans younger than myself as well.)

Perhaps the balance of light and darkness is the reason Adventures of Captain Marvel continues to be held in such esteem: it convincingly brings to life the power fantasy of the comic book superhero, without treating it as a joke or cutting corners, and satisfies those who like their heroes “grim and gritty,” at least in contrast to the source material; at the same time the line between good and evil is boldly drawn, the characters larger than life, and it is still full of the wonder and excitement of the serial medium and marvelously entertaining in its own right.

What I Watched: Adventures of Captain Marvel (Republic, 1941)

Where I Watched It: Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray release from 2017. As mentioned above, this edition has an informative commentary track including ten speakers (thankfully not all at once: each individual or group gets a chapter or two to themselves) and Matt Singer’s essay. It is, as I have mentioned in the past, exactly the kind of package the serials have long deserved and is highly recommended. However, as I don’t have a Blu-ray drive on my computer, I have once again taken pictures of the screen for screenshots (rest assured that the Blu-ray picture quality is much higher than these pictures show).

No. of Chapters: 12

Best Chapter Title: “Death Takes the Wheel” (Chapter Four)

Best Cliffhanger: Several of the commentators on the Kino Lorber release take issue with the idea that anyone would be fooled by a cliffhanger that appears to put the invincible Captain Marvel in jeopardy: wouldn’t an audience of kids in 1941 know that something as trivial as gunfire, electric shock, or even molten lava wouldn’t hurt “the world’s mightiest mortal”? Well, yes, and like the later Superman serials, Adventures of Captain Marvel solves this problem by putting supporting cast members in peril instead for most of the cliffhangers. Still, almost any serial cliffhanger assumes that the audience will play along, even if experienced viewers are well aware that the hero is going to get out of whatever jam they’ve been put in: suspension of disbelief applies here just as it does elsewhere.

More importantly, from a narrative perspective, the limits of Captain Marvel’s powers and invulnerability aren’t entirely clear at first, and the serial’s early cliffhangers serve to demonstrate just how strong he is. My favorite cliffhanger is one of these: in Chapter Two (“The Guillotine”), the Scorpion has his henchmen abduct Dr. Carlyle, one of the expedition members, and threaten him with an automated guillotine in order to extract the location of Carlyle’s lens. Captain Marvel trails the thugs to their hideout and breaks up the interrogation. However, during the fight that follows, he trips into the electric eye that triggers a subduing electric charge and starts the conveyor belt that will carry him, unconscious, to the waiting guillotine, a high-tech variation of a classic peril. The resolution illustrates the difference between typical serial protagonists and this new kind of cinematic “super” hero: instead of having Captain Marvel wake up or the conveyor turned off just in time, the next chapter begins with the blade falling onto the hero’s neck, only to break harmlessly against Captain Marvel’s invulnerable skin. I’ve complained in the past about “walk it off” resolutions to cliffhangers in which the hero is simply unhurt, but here the shot of Captain Marvel waking up beneath the shattered blade speaks for itself. Like the scenes of henchmen futilely shooting at Captain Marvel, the bullets bouncing harmlessly off, it announces that this hero plays by an entirely different set of rules.

Stanley Price Sighting: Stanley Price is included in the full cast billing that begins each chapter, but he really only has one standout scene, as one of the group of henchmen who abduct Betty after she trails them to one of their hideouts on the top floor of a parking garage. It is here that Captain Marvel engages them in the rooftop battle in which he throws an engine block at one thug and throws another off the roof. Knowing that he’s outgunned, Price flees in the elevator, only to have Captain Marvel pull the descending car back up by the cables, a feat borrowed from his comic book appearances. Price’s anxious expressions while standing alone in the elevator are, well . . . priceless (sorry, I couldn’t resist).

Sample Dialogue: “The Scorpion has triumphed and all the white infidels will be sacrificed to celebrate the victory, even the mighty Captain Marvel. . . . We need fear him no longer, for he is only Billy Batson. . . . Perhaps it’s a powerful drug or some other device which Batson uses to transform himself into Captain Marvel. . . . I must learn the secret of his transformation.” –the Scorpion, Chapter Twelve (“Captain Marvel’s Secret”)

What Others Have Said: “The saving grace is the near absence of what many serial devotees most like about Republic serials–the stuntwork fist fights. Captain Marvel was too superpowerful to take more than one punch to subdue an ordinary mortal. The screen time had to be filled with something other than punches. This serial had time for plot and characterization, as well as action. The result was what may be the world’s mightiest movie serial.” –Jim Harmon and Donald F. Glut, The Great Movie Serials

What’s Next: Join me in two weeks as I return to the subject of “Yellow Peril” with Drums of Fu Manchu!