It’s tempting to look at pop culture trends in the 1950s and ‘60s in broad strokes, shaped by after-the-fact simplifications like Toy Story 2. In that film, classic cowboy Westerns were put out to pasture (heh) with the launch of Sputnik and the beginning of the Space Race, and almost overnight children’s imaginations turned to science fiction. In the long run, I suppose that did happen, but over decades rather than months or weeks. Throughout the 1950s and much of the ‘60s, Westerns (and related frontier and outdoorsman stories) remained popular with kids (and adults), and while sci-fi eventually overtook them in relevance, there were multiple attempts to combine the two popular flavors. Gene Roddenberry may have pitched Star Trek as “Wagon Train to the stars” and codified space as “the final frontier,” but he wasn’t the first to make the connection. Craig Yoe, prolific historian and anthologizer of comics, has produced a fun and informative volume in Space Western Comics, reprinting and contextualizing a run of adventure stories combining cowboys and aliens from the 1950s. It’s perfect reading for Vintage Science Fiction Month.

It’s worth noting that the term “space Western” was sometimes used (derogatorily) in sci-fi publishing and fan circles to describe stories that were just the same old formulaic good guys confronting bad guys dressed up in otherworldly verbiage, with rayguns replacing six-shooters and spaceships replacing horses. (Star Wars was attacked in the ‘70s by purists along exactly those lines, but at least Star Wars had considerable artistry on its side; in the ‘50s the white hats vs. black hats approach was strictly the domain of hacks.) But there were some literal space Westerns as well that combined the terminology and iconography of both genres into a single, (mostly) coherent story world. (I wrote about this weird subgenre several years ago and went into detail on the movie Cowboys & Aliens, at the time the most current example.)

Westerns in the first half of the twentieth century weren’t limited to the Old West. Real-life ranches and cowhands were enough of a reality that so-called “modern Westerns” could tell stories of pure-hearted (often singing) cowboys fighting cattle rustlers, land-grabbing oil or radium speculators, and other unscrupulous villains while using up-to-date technologies like automobiles, airplanes, and radio. While fanciful, these modern Westerns ostensibly took place in the “real world” of the 1930s, ‘40s, or ‘50s. Naturally, some of the same futuristic devices that were appearing in contemporary serials and comic books—miraculous rays, rockets, and the compelling but imperfectly-understood “television”—made appearances in the modern Western setting as MacGuffins or mysteries that needed to be unraveled. A cycle of “gadget Westerns” ran its course in the serials of the 1930s, but none of those involved actual space travel or alien visitors. The Phantom Empire, which famously sent Gene Autry underground to confront an ancient, advanced civilization miles beneath his ranch, stands out as an example of the Western exploring inner, not outer space.

So it is perhaps not surprising that the still-popular Western genre, chasing after trends, would incorporate UFOs, space travel, and alien life in an attempt to hold fickle audiences’ attention. And it is even less surprising that comics—a business with low costs and quick turnaround compared to the movies—would be in a position to take advantage of the brief moment when cowboys and spacemen appeared to be on equal footing (at least with the allowance-spending children of America).

In 1952, based on a suggestion from Charlton co-publisher Ed Levy, the already-extant Cowboy Western Comics changed its title to Space Western Comics (a common practice: instead of starting a new series with issue number one, it was believed that high numbers were more attractive to newsstand buyers, as they suggested a successful track record). Walter P. Gibson, the prolific writer and magician who developed and ghost-wrote The Shadow for Street and Smith, among many other projects, wrote and edited the adventures of “Spurs” Jackson, a rancher and electrical engineer whose ranch becomes the center of zany outer space adventures. (Shades of Gene Autry!) Artists John Belfi and Stanley Glidden Campbell provided the illustrations. The book reverted to Cowboy Western after only six issues, but a couple of stories starring Jackson from later issues are included in Yoe’s volume for the sake of completeness, as are two space-themed stories from Buster Crabbe’s comic book. (Crabbe had, of course, played both Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers in addition to cowboy roles, so this made perfect sense.)

Space Western Comics begins with the Space Age already underway: flights to the moon have become routine, and a space station orbits the earth. “Spurs” Jackson is a character made to have adventures: unmarried and wealthy enough to occupy his free time inventing in his “secret lab,” the rancher-slash-engineer is charged with maintaining a 1000-foot-tall radar tower on his land (a government connection that serves to fuel several later stories), while leaving the day-to-day operations to his foreman, Hank Roper, and the Indian Strong Bow. The radar tower, which helps guide the lunar flights, attracts the attention of spaceships from Mars, who abduct the three men and take them to the red planet. There, they are presented as evidence that the Martians have conquered earth, a pretext that puts the scheming Korok on the throne of Mars instead of the rightful Queen Thula. This is classic space opera material straight out of Edgar Rice Burroughs, but the Western theme eventually pays off: Korok’s throne room is protected by a force field that prevents any metal from penetrating, so Martian weapons and the earthlings’ six-shooters are useless, but Jackson’s whip, Roper’s lariat, and Strong Bow’s bow and arrow, all non-metallic, win the day. For putting things right, Thula offers Jackson a position as her prime minister, but he can’t stay on Mars for long: ranching is an all-day job.

Some of the stories in this volume depend on the romance and exoticism of exploring other worlds, but in many of them the trouble is closer to home. Would-be alien invaders, Communist spies (sometimes disguised as aliens), criminal gangs, and even Nazis threaten the peace of the Bar-Z ranch. The desert makes for a compelling setting, full of isolated canyons and desolate flats, remote enough from civilization that no one in the cities would believe the stories but close to the Army’s testing ranges and bases so there are always plenty of troops and weapons ready to take charge of the surviving villains. As silly as the premises of these stories often are—rock men, plant men, and underground super-moles are among the aliens Jackson encounters—Gibson packs them with twists and clever problem-solving. Like a good engineer, “Spurs” Jackson out-thinks his opponents as much as he out-fights them (although he’s not above setting off an atomic bomb or two if that’s what it takes).

And frequently the twist is kept from the reader until the most dramatic moment, revealing that Jackson had his enemy’s number the whole time. In one of several text pieces, slavers from the planet Letos are foiled by a ship full of humanoid robots supplied by Jackson—“robots” who are actually humans in bullet-proof robot costumes. (Postal regulations required the text pages to secure favorable magazine rates; they were most often filled with editorials or letters columns, but short prose stories were not uncommon. The two-pagers Gibson provided for Space Western Comics are clever pulp miniatures, often written in the folksy voice of characters from around the Bar-Z. I think they would stand up well with the humorous sci-fi of Henry Kuttner and his contemporaries, should anyone think to mine comics’ text pages for anthologizing. Today, Alan Moore seems to be the only comics creator left with much affection for this archaic institution.)

Jackson isn’t the only savvy operator, either: Strong Bow is written as a more sophisticated and educated character than his Tonto-like dialogue might suggest. In more than one story, Indians appear to arrive from space, claiming to be heroes from the past or remnants of lost tribes, inviting the local Indians to overthrow the United States government. Of course, Strong Bow sees right through them, even if he might pretend to go along with the plan. (Although Space Western Comics predates the infamous Comics Code, it’s still as pro-government, pro-American, and pro-law and order as anything produced under the Code. The government and military in these stories are never less than righteous and upstanding, give or take a traitor or two in their midst, so nothing as subversive as suggesting Indian activists might have a point ever enters into the discussion.)

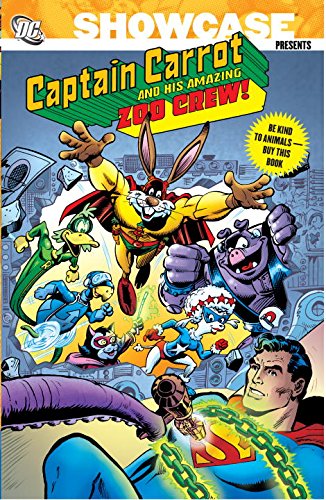

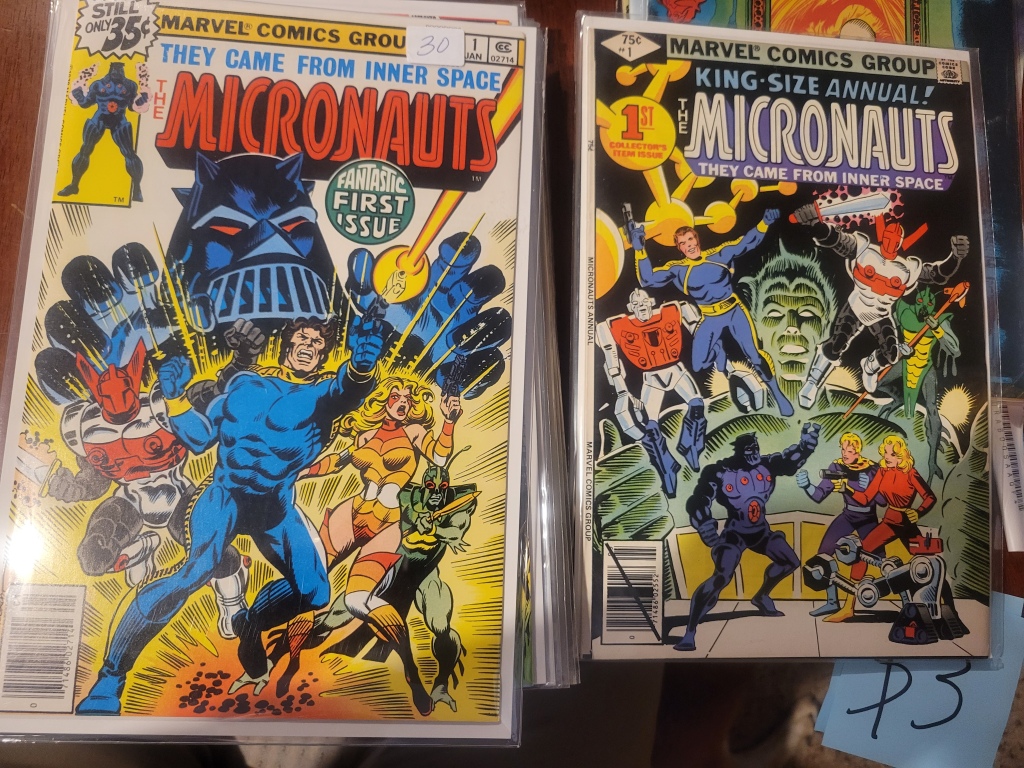

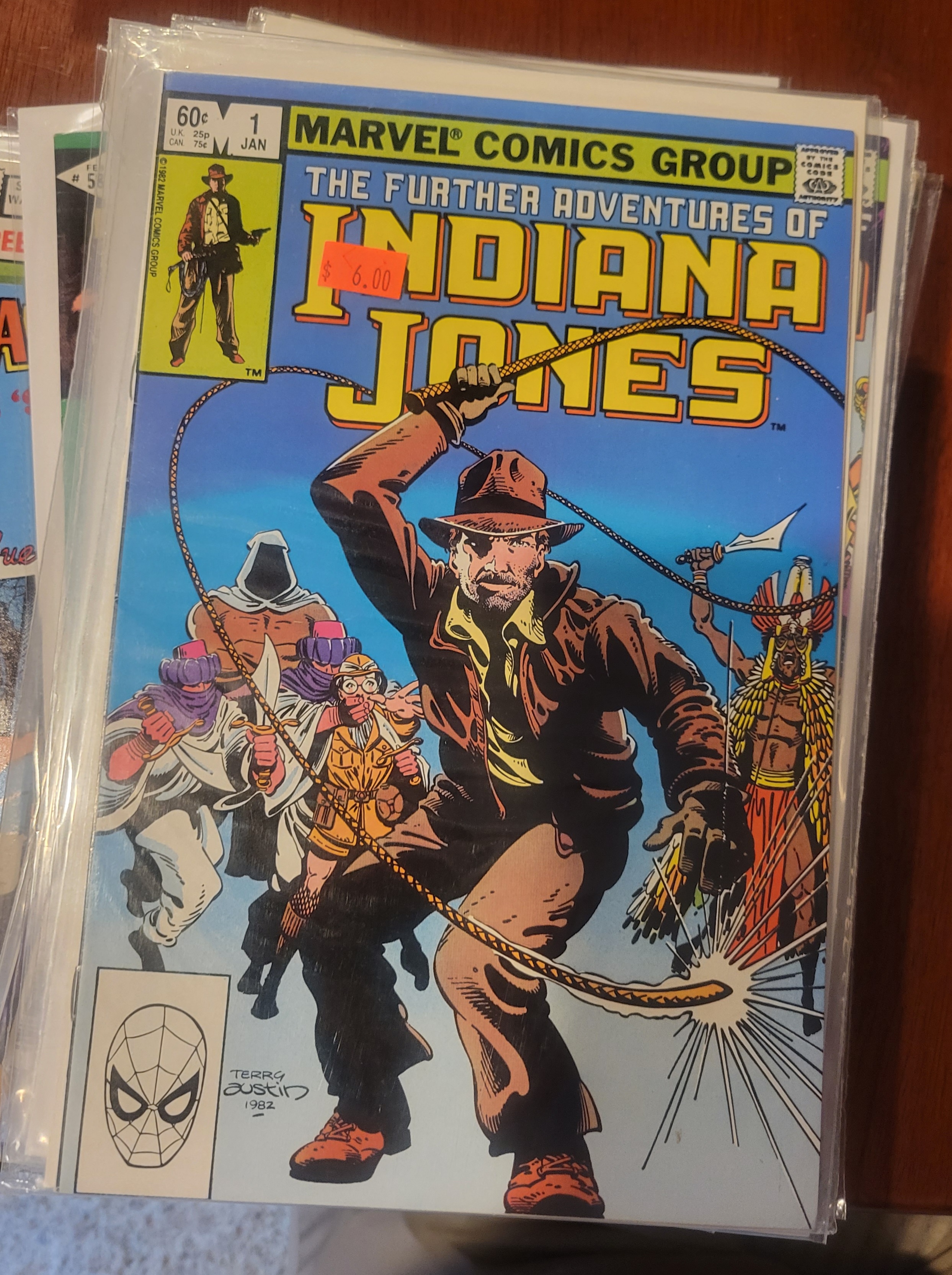

As I’ve alluded to in past articles, comics are a natural medium for the kind of mash-up represented by Space Western Comics: the visual shorthand that is a vital part of comics vocabulary lends itself to mixing and matching. Without attempting to catalog every example of the space Western from later comics, I’ll point to Terra-Man, a cowboy-themed villain from Superman comics. Abducted by space aliens as a child in the Old West, Terra-Man returned to earth with high-tech equivalents of the cowboy’s accessories and an alien winged horse. Current comics have embraced this kind of meta-referentiality with a vengeance, remixing popular iconographies of all kinds with kaleidoscopic variety. Sometimes it’s overwhelming, but I remind myself of being a comics reader in the 1980s, when the Big Two publishers seemed to be embarrassed by anything too “wacky,” and it was left to the independents to publish books like Marc Schultz’s Cadillacs and Dinosaurs (or for that matter, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, as much a mash-up as a parody). I prefer the current acknowledgment of the medium’s silly roots, without the po-faced need to pretend that it’s all serious business.

By now, the proclamation that “comics are supposed to be FUN” is a tradition within comics that is up for grabs, just like every other past genre or practice that is ripe for revival, rehabilitation, or reinvention. Sometimes that means characters like Howard the Duck or Detective Chimp are given equal time with Iron Man or Wonder Woman; sometimes it means weaving disparate, contradictory threads into ambitious multi-layered story arcs that breathe new life into one-off concepts like the Green Team. Signifiers of “comics FUN” include (but are not limited to) ghosts, robots, dinosaurs, gorillas, and, of course, cowboys and rocket ships. Craig Yoe plays up how quaintly ridiculous the stories in Space Western Comics are, and is clear-eyed about the mercenary motives that led to its original creation. But he is equally up-front about how imaginative, breathlessly exciting, and yes, FUN, these stories are, and he has performed a valuable service by putting them together in a handsome and easily accessible package.