It seems like it should be easy: “space cowboys” such as Han Solo and Mal Reynolds are essentially Old West gunslingers dropped into the cockpit of a spaceship, so why shouldn’t it work the other way around: a robot on horseback or a space alien on a stagecoach? Despite the longstanding popularity of both Westerns and science fiction, the number of films that successfully bring the two genres together in this way is surprisingly small. To be sure, ghost stories, tall tales, and bloody violence are all established parts of Western lore, and some great movies have been made exploring these themes, but the “weird Western” typically explores the boundaries of fantasy and horror, myth and history, rather than science fiction. It turns out that it’s easier to move the Old West into outer space than vice versa.

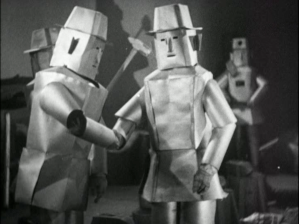

Undoubtedly, the cinematic grandfather of all such hybrids is the 1935 serial The Phantom Empire (of which I have written more extensively elsewhere), in which singing cowboy Gene Autry runs up against members of a super-advanced underground civilization. In their book The Great Movie Serials, Jim Harmon and Donald F. Glut characterize The Phantom Empire as the beginning of a cycle of “zap-gun Western” serials. However, the other examples they cite, such as Tom Mix’s final film The Miracle Rider, involve super-science of purely human invention, and lack the sense of weird mystery and contact with alien forces that makes The Phantom Empire so distinctive.

Perhaps the reason there have been so few overt fusions of science fiction and the Western in film is that such a hybrid is redundant: once science fiction (especially in the pulpy, action-adventure mode that has dominated popular film-making) took over the Western’s role as the main arena for playing out America’s myths and fears, it borrowed wholesale many of the plots and character types associated with the older genre, effectively replacing it. Good guys (almost exclusively white in the early years of both genres) and bad guys (sometimes literally alien, sometimes white men whose greed had overcome them); a thirst for exploration and conquest, usually in the name of civilization but often identified with commercial interests; and a sense of isolation, of being separated from the routines and mores of the old world (including meditations on the softening, corrupting influences of civilized society), were all notable features of both the Western and early science fiction, to the point that “horse opera” could be updated to “space opera” without any misunderstanding on the part of audiences. The “edge of civilization” was constantly moving outward: Star Trek’s description of space as “the final frontier” is illustrative.

Show creator Gene Roddenberry pitched Star Trek as “Wagon Train to the stars.” A few episodes, such as “Spectre of the Gun,” made it literal.

Besides the gunslinger, other characters, such as the alien other, the damsel in distress (or the hooker with a heart of gold in racier manifestations: neither genre had much use for well-developed female characters, as pioneering was considered man’s work), the white man “gone native,” the amoral company man, and the wise tribesman (often the last of his kind, given a tragic nobility once no longer a threat) were translated easily. Science fiction, arriving as it did in a period of both rapid dissemination of ideas and ready access to literature of the past, became a clearinghouse of genre storytelling, absorbing themes and tropes like a sponge. From this point of view, it’s only natural that Terry Gilliam could describe Darth Vader as “the cowboy with the black hat,” that Flash Gordon’s Princess Aura fits the mold of the femme fatale, and that Seven Samurai could be remade as both a Western and as a space adventure. Ultimately, callow, daydreaming farm boys are the same everywhere, whether from Texas or Tatooine.

In that case, the distinction between the two genres is one of iconography, and iconography flourishes in visual media: comic books and cartoons have always been friendly to the robot in a cowboy hat, as have the pop surrealism movement and the artists who contribute to sites like DeviantArt. When it comes to mixing and matching, Western and sci-fi are primary colors that can be laid on in broad strokes.

Both literary and cinematic science fiction have had to work to absorb Western motifs, however: all but the most fantastic stories attempt to rationalize the mixture of Old West and New Frontier, and here the difference between the two genres is a clear obstacle.* The Western is rooted in a specific time and place, and once that historical moment was over, the Western became a genre about the past (one reflecting contemporary attitudes, to be sure, but almost always focusing through the lens of history); science fiction, especially in the early Space Age, was about the future, and whether focused on the promise of exploration or the horror of nuclear war, it used speculation about the future to examine the current moment. In short, both forms stood in the present, but the Western looked into the past, either searching for some imperialistic original sin or retreating into comforting nostalgia, while science fiction looked into the future, projecting either our hopes or fears.

Given that difference in emphasis, science fiction has often chosen to visit the Old West by means of time travel or alternate history. The “steampunk” movement has produced a wide variety of literature, some of it great, but on film it has been too often a faddish visual template that can be applied to the same old pulp storytelling: the result has been ambitious failures like the film version of Wild Wild West or “high concept” dreck like Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter. (Complaints about the perceived hackiness of combining the two genres aren’t new: Wikipedia’s “Space Western” entry notes pulp-era efforts to stamp out lazy updates of Western plots in sci-fi garb, including one magazine’s ad campaign claiming “You’ll never see it in Galaxy.”)

Better are films that find ways to repurpose the trappings of the Western, like Westworld, in which the Western setting is a fiction within the fiction, or Serenity (the belated finale of television series Firefly), which makes explicit both the themes of colonization and post-civil war disillusionment that are a part of the Western. In both cases, the adoption of Western dress and lingo are made to seem not only organic to the setting but essential to the stories being told: both use science fiction to interrogate the Western, and by extension mythmaking in general.

* Even excursions into outright fantasy don’t always pass the laugh test: I invite you to consider the short-lived 1987 cartoon series BraveStarr:

I’ve also just become aware of a 1999 film called Aliens in the Wild, Wild West that doesn’t look too promising; although I haven’t seen it, an imdb reviewer calls it “one of the top ten worst movies I have ever seen.” Tellingly, like The Phantom Empire and like BraveStarr and similar cartoons, Aliens in the Wild, Wild West appears to have been made primarily for children.

Next week, I’ll look at a recent example of the genre, 2011’s Cowboys & Aliens.