Dr. Alex Zorka, one of the world’s most brilliant scientific minds–the most brilliant, according to him–is a proud man. The sacrifices he has made for his work, the depth of his genius, and above all his monumental ego will not allow him to countenance turning over his fabulous inventions to the government–not even on the eve of war, when the world is about to become much more dangerous. Zorka’s wife, Ann, has tried to convince him to turn back before his research takes him too far, even bringing his former partner, Dr. Mallory, to help plead the case. Zorka’s latest invention consists of a small disc that can be planted anywhere (or on anyone), and a mechanical spider that homes in on it; when the spider comes into contact with its target, a small burst of smoke paralyzes anyone within range with a unique form of suspended animation. Mallory urges Zorka to give the disc technology to the government, but Zorka already has a buyer lined up; what they choose to do with it is of no concern to him. Gloating later to his assistant, Monk (an ex-con Zorka freed and disguised, making him indebted to him and practically a slave), Zorka shows off his latest device, a “devisualizer” belt that renders its wearer invisible. “Now, as the Phantom, there is nothing that I cannot do.” Zorka’s pride is already tipping into megalomania, and he hasn’t even revealed his killer robot to the world!

After Dr. Zorka disappears (into a secret laboratory hidden in his house) and then fakes his own death, Captain Bob West of military intelligence gets involved, interviewing Ann Zorka and Dr. Mallory. A nosy reporter, Jean Drew, shows up, but West stonewalls her. When West and his partner Jim Daly load Ann into a plane to take her to identify her husband’s body, Jean stows away, hoping for a scoop. None of them realize that Dr. Zorka, invisible, has planted one of the magnetic discs on the plane with the idea of paralyzing his wife and then claiming her body (under a new identity) to keep her from talking to the authorities. The plan backfires, paralyzing Daly while he’s piloting the plane and causing a deadly crash. Ann dies, and in his grief and madness Zorka blames West and the government. “They shall pay!” he rants in one of his many diatribes. The stage is set for Dr. Zorka to wreak scientific vengeance while outmaneuvering both the G-men and the foreign agents who still hope to obtain his invention.

His final serial appearance, The Phantom Creeps stars the great Bela Lugosi in full scenery-chewing mode as Dr. Zorka. From the beginning, Zorka’s main emotional note is aggrievement: his scientific peers don’t appreciate his genius, he doesn’t owe anything to the government, they’ll see, he’ll show them all, blah blah blah. It’s a character type that was as much Lugosi’s bread and butter as the suave vampire that brought his initial fame. After Zorka’s wife dies and his various plots are foiled, his mania becomes more and more pronounced and his goals proceed from selling his invention for riches to conquering the world, or, failing that, destroying it. The only character he regularly interacts with is poor, put-upon Monk (Jack C. Smith), who follows him out of fear as much as any sense of loyalty. Constantly complaining that he’ll be caught and thrown back into Alcatraz (“It’s where you belong,” Zorka answers dismissively), Monk waits for the opportunity to sell out his boss, and he almost turns the tables more than once before Zorka gets the upper hand again. It is to Monk (and thereby indirectly the audience) that Zorka explains his various devices, revealing the highly volatile element that powers his inventions: the element is deadly unless kept in a shielded box, and even when opened a crack to siphon off its energies it emits deadly fumes. “They must never know about you, the source of all my power,” Zorka says to the box lovingly. But of course “they” do find out, and the box becomes the main MacGuffin of the plot, changing hands between the spies, the G-men, and back to Zorka as they all scheme to hold on to it.

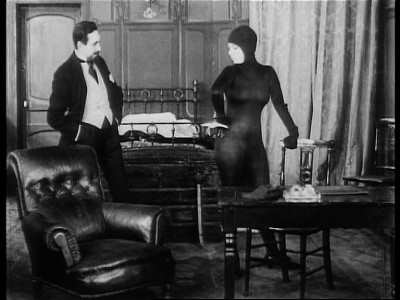

It is perhaps not surprising that the best-known element of this serial is not the precious element in its box or the invisibility device that inspired its title, but the robot (or “iron man”) who serves as Zorka’s guardian and sometimes attack dog. Inside the robot costume is 7’4″ Ed Wolff, a former circus performer who specialized in giant roles. The robot’s appearance is, on one level, ridiculous, a large humanoid machine with a grotesque molded face on an oversized head, a design choice that goes against our usual idea of robots as being more streamlined than their human models (perusing illustrations of early attempts at building robots reveals that many designs made up in baroque style what they lacked in functionality). But however ugly, it is clearly the most visually distinct element in the film. To be charitable, it resembles a pagan idol, and its role in the story is akin to that of a temple guardian, never leaving its one room until the very end of the serial. If serials are part of the modern mythmaking machinery by which ancient fables are dressed anew in contemporary garb (and I think they are), it makes sense that the iron man would continue the lineage of such pre-Enlightenment automatons as the golem or Talos, the bronze warrior from Greek mythology. (Surprisingly, Zorka doesn’t end up dying at the hands of the iron man, an ironic comeuppance that would have been perfectly in line with this kind of storytelling; the robot remains under control to the end. Zorka’s fate is a little more, ahem, explosive.)

The dynamic of the square-jawed hero (Robert Kent as West) and the gutsy reporter who will take any risk for a story (Dorothy Arnold as Jean Drew) is one that has shown up in many serials and pulp narratives (including the other Lugosi serial I’ve covered, Shadow of Chinatown). Filmmakers in the ’30s and ’40s seem to have loved brassy “girl reporters,” partially as a career choice open to independent women that allowed for zany adventures and partially for the opportunity for more level-headed male characters to put them in their place. The Phantom Creeps patronizes Jean an average amount I’d say, with Bob West tweaking her resolve with comments like, “That isn’t like a hard-boiled newspaper girl to faint!”

At least West is motivated by official secrecy to keep her silent, urging Jean to keep details to herself even as her editor hounds her for something fit to print. West’s partner Daly (Regis Toomey) seems more irritated by having a girl nosing around and becomes especially suspicious when he observes Jean leaving a warehouse to which he had trailed the spies (caught unawares by them, she had posed as a fellow operative, hoping to find Zorka’s invention and sell it herself). “Save it for Captain West,” he says: “He likes fairy stories.” Finally, when Jean is rewarded for her cooperation with the story of her career, West compliments Jean’s restraint by saying, “The hardest job for a reporter is the suppression of timely news.” In other words: loose lips sink ships.

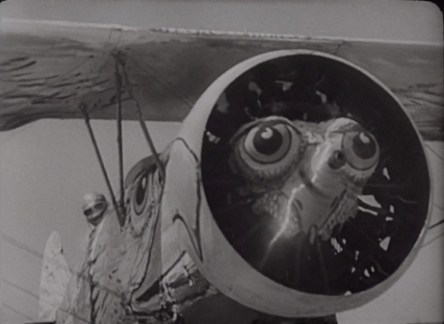

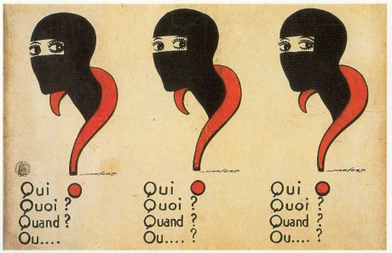

The spies, to whom Zorka had initially hoped to sell his invention and who later try to steal it outright, have a few nice touches. The only one of the field agents who has much personality, Rankin (Anthony Averill), is sort of a spearhead villain, indistinguishable from a typical movie gangster, but the head of the spy ring, Jarvis (Edward Van Sloan) is a bit more of a character. The spies maintain an “International School of Languages” as a cover, from which they broadcast cryptic coded messages by radio. As is frequently the case, the spies’ foreign superiors go unnamed except for vague mentions of a “leader” or occasionally “His Highness.” I wonder which foreign governments they might have been thinking of in 1939? I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out this incredible flying costume Jarvis wears in Chapter Four (“Invisible Terror”) during a brief moment when the spies are in possession of the box and try to fly it out of the country.

The Phantom Creeps has many elements that I love in the serials: crazy gadgets, distinctive visuals, colorful characters, and a great villain. The tone, from the ominous theme music to the shadowed interiors of Zorka’s mad science lab (full of Kenneth Strickfaden’s whirling, sparking electrical contraptions) is closer to Universal’s famous monster series than the typical action serials of the day. There is also plenty of drama to be mined in the confrontations of the individual characters and their competing goals; even the small-time spies and beat cops get little character moments as they deal with the unknown menace of the “Phantom.” So I really wish I liked it more, and it saddens me to report that these promising parts rarely coalesce into a satisfying whole.

It’s hard to put my finger on why it fell short for me. Part of the problem is that there is just too much going on: too many characters, too many of whom change their behavior or loyalties depending on the scene in order to keep the story going. The way the action returns again and again to a few locations makes it feel like it’s spinning its wheels (considering that Zorka’s robot never leaves his house, where it is hidden behind a sliding panel, it’s surprising how much use it gets, since characters keep finding reasons to go back there). The ways in which the characters encounter each other are often dependent on coincidence: one might think there was only one road in California for the number of times characters pass and recognize each other, setting off yet another chase (“There go two of the spies in that car!” is a typical line of dialogue). I guess it comes down to too much filler, not enough killer.

There is also the general shabbiness that many serials display, amplified by the sense that The Phantom Creeps is made up of bits and pieces thrown together or borrowed from other productions. Other serials have featured invisible characters and made them spookily effective, but only a few scenes in this truly use the “Phantom” conceit in a thrilling or atmospheric way. (The invisibility effect is little more than a double-exposed smudge of light, or occasionally a shadow.)

The use of stock footage to ramp up the threats to our heroes also becomes excessive (and familiar–it surely doesn’t help that I’ve seen this boat crash, that building fire, and even that shot of the Hindenburg disaster in other serials) as it approaches its literally cataclysmic finale. Or perhaps it’s simply how generic everything seems; one of the best parts of The Phantom Creeps is a short flashback in which Dr. Zorka reveals the mysterious radioactive element that powers all of his inventions: it fell to earth in Africa as a meteorite centuries ago, where it lay buried in the ground until Dr. Zorka arrived to dig it up. The visual of Zorka in a protective hazmat suit, lowered into a crevice by native bearers and chipping the sparking, smoking stone from the rock is specific to the story in a way that too much of it simply lacks (wouldn’t you know it, that sequence turns out to be lifted from the 1936 Lugosi/Karloff feature The Invisible Ray).

What I Watched: The Phantom Creeps (Universal, 1939)

Where I Watched It: A two-tape VHS set from VCI’s “Classic Cliffhanger Collection”

No. of Chapters: 12

Best Chapter Title: “To Destroy the World” (Chapter Twelve)

Best Cliffhanger: At the end of Chapter Eleven (“The Blast”), spies Jarvis and Rankin have taken off in their car with the meteorite (and, unbeknownst to them, Zorka in his invisible state); spotting them, West and Jean follow, with Jean driving. Jarvis pulls up at a barricade: the road is closed for blasting, but the workers let the car through. The workers continue preparation for blasting, and because of a faulty detonation plunger one of them lights a long fuse. Just then, West and Jean drive up and spot the barricade. “It may be a trick to stop us,” West says, instructing Jean to keep driving. Despite the protests of the workmen, they drive through the barricade; mere moments later–kaboom!

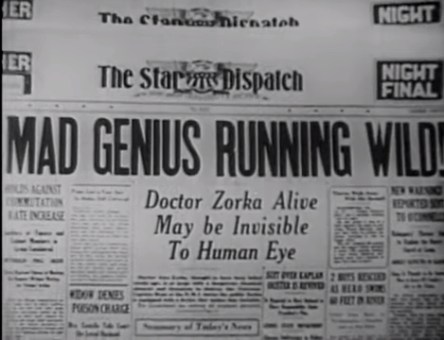

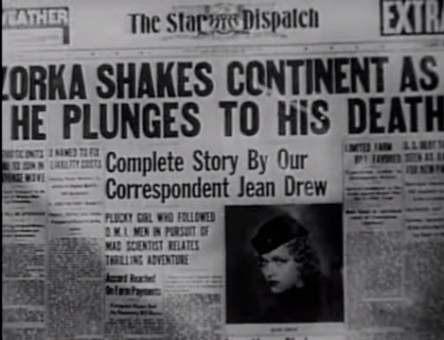

Breaking news: Like many serials, especially those featuring reporter characters, The Phantom Creeps has some great on-screen newspaper headlines for quick bursts of exposition.

SCIENTIST AND WIFE MEET DEATH SAME DAY IN DIFFERENT ACCIDENTS!

MAD GENIUS RUNNING WILD!

ZORKA SHAKES CONTINENT AS HE PLUNGES TO HIS DEATH

Don’t forget the funny pages: The Phantom Creeps was adapted (very freely) in an issue of Movie Comics; the publication retouched frames from the movies, turning them into comic panels. The eight-page story takes liberties from the very first page, putting Zorka’s laboratory in an old castle instead of a house, and in this version “Phantom” is the robot’s name. Some things never change. The entire story can be read at the blog Four-Color Shadows.

Sample Dialogue:

Monk (invisible, having stolen Zorka’s devisualizer belt): I’m free, Dr. Zorka! I’m stronger than you now! Stronger than the police! You’ll never make a slave out of me again. Ha ha ha!

[Zorka zaps Monk with a “Z-ray” and makes him reappear, briefly incapacitating him]

Zorka: You traitor! You didn’t know that you too had been sprayed with my invisible gas. Get up on your feet! . . . You belong to me! You can never escape me! Go!

–Chapter Seven, “The Menacing Mist”

What Others Have Said: “The contribution of The Phantom Creeps to later serials was an auto chase in which a 1939 black Nash pursued an ancient touring car. The appearance of a vintage vehicle in a chase was a sure sign that sooner or later it would go over a cliff and burn. New cars didn’t match those in crashes in the stock-film library, and stock shots were meant to last many years.” –Raymond W. Stedman, The Serials: Suspense and Drama by Installment

What’s Next: For what will probably be the last installment of this series for the summer, let’s check out the proto-Raiders adventure, Secret Service in Darkest Africa aka Manhunt in the African Jungles!