At night, the Turbo Fish Cannery became a monolithic wall of shadow. Only a few pinpoints of light on the roof of Processing Facility No. 1 gave away the team’s presence. Ping! The quiet sound of waves gently lapping in the bay was interrupted by Aki’s cell phone. With an apologetic gesture to his fellow Aquarian watchers, he took the call. “Sweetheart! Is something wrong?” His voice always sounded urgent at a low whisper; but did his heart beat faster in anticipation of the evening’s duties or in excitement over hearing from his fiancée?

Sachiko spoke from the other end: “The news reported a sighting, up the coastline near the Canadian border. Are you sure you’re in the right place?”

“The border? That’s miles away.” Aki looked nervously at the huddled watchers; most of them had their attention on the still-dark bay, but Campbell was looking at him expectantly. For a moment, doubt gnawed at him, but he shook it off. “No, it must be something else. My charts haven’t been wrong yet. He’ll be here.”

“But the news said–”

“We’re monitoring the news here,” he lied and immediately regretted the deception. “They’re wrong. Don’t worry–”

An agitated murmur from the watchers drew his attention to the bay; the water was beginning to foam and churn with activity. Distantly, a bell rang as a buoy was rocked by the waves: something was moving through the water.

“Something’s happening. I have to go, dear.”

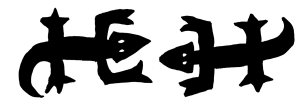

“Stay safe, Aki. I love y–” Aki ended the call and turned his attention to the churning waters of the bay and the printout unscrolled in front of him. Red, blue and green lines zig-zagged up and down like an EKG readout against black hash-marks keyed to time and location. Relief and pride mingled within him: right on time.

The hushed excitement gave way to a collective gasp as the waves surged forward into the inlet, the whitecaps standing out against the dark water. The surface split as a scaly, reptilian form emerged: first the vane-like dorsal plates, then the spiraling horns that crowned a massive, leonine head, then the towering, erect body: the giant beast code-named Regulus. It roared to announce itself, a thunder like the cry of a prehistoric bird with the resonance of a deep gong that could be heard for miles.

The team sprang into action; as always, Aki’s most serious contribution was made before the beast’s arrival, predicting its path and most likely point of emergence. Other members of the team consulted laptops and tablets and spoke into wireless headsets, turning on klieg lights around the cannery’s power lines. The whir of helicopter blades in the distance preceded the burst of flares, guiding Regulus toward them. The beast slowly but surely changed course, paddling until it reached the shallow part of the bay and its feet made contact with the sandy bottom. Then it lurched forward, displacing mountainous waves before it.

At that moment, the door to the interior stairwell opened and an imposing figure emerged: Mosha, Turbo’s Chief of Security. After a few abrupt words from Mosha, Campbell began shutting down the operation. “Mister Turbo desires to shift the focus of his involvement with Project Aquarius,” Mosha said, an explanation that explained nothing.

“But the power lines–” Aki said, still not understanding. After his predictive work, was the beast now simply going to be let go?

“That’s not your concern,” Mosha said with finality.

At Campbell’s instructions, the lights were turned off and the sound of helicopters faded into the distance; no more flares were lit. In the moonlit shadows of the bay, the Aquarian beast Regulus lost interest in the suddenly dark cannery and made his way back to the open sea.

“I still don’t understand why you’re not out there,” Sachiko said to Aki as they stood on a balcony overlooking the city. It was a good vantage point to observe the convergence of Regulus and Antares; it was an unseasonably warm, sunny day, one of the few the city would have. Only a few wispy clouds floated in the sky.

“I thought you didn’t like me being in the field,” Aki said, scanning the horizon with a pair of binoculars. “We’re safer up here, and I can be with you while we wait.”

“That’s not what I mean,” Sachiko said, squirming. “Of course I like being able to watch with you, but I know how important tracking the Aquarian beasts is to you.”

“Craig is tracking today’s convergence,” Aki said. “He is completely capable.” He continued searching the horizon, looking for telltale signs of activity. It was partly professional interest–he now tracked the Aquarian beasts as part of Roman Turbo’s private operation–but he wouldn’t have missed it anyway.

Sachiko gently lowered the binoculars from Aki’s eyes and turned him toward her. “I hope you haven’t given up tracking in the field for my sake,” she said seriously, looking into his eyes.

“Huh? No, of course not.” He turned back to the view over the city. “Mister Turbo has given me a very good opportunity to be on the ground floor of something new he is building, and I have to take that seriously. Besides,” he added absently, “if everything works out we won’t have to depend on the Aquarian beasts for much longer.”

There they were: Antares was the first to break the surface of the water, near the public beach. The area had been cordoned off. It seemed unfair to block the beach on one of the city’s rare sunny days, but crowds had turned out anyway to watch the spectacle, and as the great four-legged beast trundled forward, the mass of humanity pressed against the barricades to get a good look. The Aquarian beasts were beloved, and their arrival often resulted in impromptu holidays like this: schools and offices were closed, and public safety crews were called into action to control the crowds and help channel the enormous visitors.

“Hmm?” Aki asked, staring at the spiky, domed carapace that made Antares resemble a moving fortification. “Did you say something?”

“I said, why wouldn’t we want to depend on the Aquarian beasts?” Sachiko sounded petulant.

Aki lowered the binoculars again and forced himself to give her his full attention. “I know it is difficult to understand,” he said. He had to remind himself that Sachiko was a civilian. She didn’t see like he did how complex the beasts’ migration patterns were, and how much the economies of the Western Seaboard–the entire Pacific, in fact–had been reshaped around their presence. “Mister Turbo says that the Aquarian beasts won’t be around forever. He thinks we’ve become soft, unable to do things for ourselves. The new project is designed to put humanity back in the driver’s seat.” He caught a glimpse of movement: Regulus emerged and joined Antares in an open space that had been cleared for renewal. A stockpile of industrial runoff sealed in drums sat clustered in the center; beyond that, nothing but weedy vacant lots and expanses of cracked pavement stretched before the two beasts.

Regulus made landfall and saw Antares, already gorging himself on the drums of waste: the beast’s powerful metabolism would convert the toxic chemicals into safe organic compounds. Regulus, approaching, roared in greeting and stood rampant. Antares, finally noticing the new arrival, roared in return and nosed half of the drums toward Regulus. While the Aquarian beasts shared the bounty, workmen rushed into the open area to prepare for the next phase of the convergence.

“I’ve heard what Turbo says. It sounds as if he wants to get rid of the Aquarian beasts because he can’t exploit them himself.”

Aki only half-heard her. He was riveted to the spectacle of Regulus dragging his tail across the open space, guided by workmen who looked like hardhat-wearing ants by comparison: Regulus’s tail left an enormous furrow in the dirt behind him, which would become a new subway tunnel. Meanwhile, Antares dug into the ground, making holes that would become the foundations of skyscrapers. With his plow-like nose Antares pushed the loose soil into embankments, and the hollow conical scales he shed would later be turned into hip coffee shops and independent bookstores. An entire neighborhood would spring up after this convergence.

“An entire city shut down,” Aki said. “Mister Turbo’s earth-moving equipment could do this work in half the time, and with half the manpower it takes to steer these creatures.”

Sachiko put her arms around Aki, who continued watching. “But what would the city do for power?” she said. “Look, Regulus is about to charge the batteries.” Regulus had solar power stored in his belly, which was covered with plates of a translucent, crystalline substance. The crystals glowed from inside, giving the impression that Regulus’s scaly hide was but the rocky rind covering the outside of a geode. Regulus approached the heavy-duty power lines that led to the city’s storage batteries: as the crystals made contact with the lines, stored-up power flooded through them. Regulus appeared to have absorbed even more solar energy than usual during his equatorial season; this would provide electricity to the city for at least the rest of the quarter.

“Just think what Turbo Power and Light could do if they were able to synthesize the material Regulus’s crystals are made from!” Aki said. “Then we could control that power, instead of those mindless animals!”

Sachiko raised an eyebrow and relaxed her grip on Aki. “You used to love the Aquarians. . . . I don’t think I like the influence Roman Turbo is having on you.” She was looking at him in a way she never had before.

Aki laughed lightly. “You’re so sentimental, Sachiko. You should listen to the engineers on my new team; it would really open your eyes.”

While Aki and the rest of the project team stood on the platform in the shadow of their colossal creation, waiting for the ceremony to begin, Aki couldn’t help but wonder if Sachiko was watching, wherever she was. The last few weeks had been such a whirlwind that he had hardly had time to think about her, or to go over their last few conversations in his mind to figure out what had gone wrong. Maybe that was the problem. There was a new woman in his life, at whose feet he stood: two hundred-odd feet of steel and chrome, as beautiful and hardened as an Ayn Rand heroine, and she commanded all of his time and attention.

The crowd began to grow restless; the field on the edge of town that formed the staging area had filled with curious onlookers since early that morning, when the silver and gold colossus had first appeared there. For the moment she was cloaked by banners hung from cranes as tall as she was: on one, a stylized picture of Antares devoured the word JOBS; on the other, Regulus trampled the word FREEDOM.

At zero hour, the PA switched from warm-up music to the voice of an announcer: “Ladies and gentlemen . . . you know him from Turbo Fisheries, the Turbo Financial Network, and the Turbo Museum of Modern Art . . . author of Turbo: The Book . . . a man of the people . . . please welcome . . . Rrrroman Turrrbo!”

The man himself emerged from between the banners, flanked by Mosha and the rest of his security detail. He approached the microphone like an old friend and began speaking off the cuff as if inviting each and every member of the crowd into his confidence. “Thank you, friends, for coming out today,” he began after the cheering and applause had died down. “If we’re lucky the rain’ll hold off a little while longer, but y’know, if we do get a storm, I think you’ll find this little lady–” he jerked his thumb backward to indicate the two-hundred-ton figure that loomed over them–“makes one hell of an umbrella, you know what I mean?”

Chuckling at his own joke, he continued. “You know, when we announced our intentions, a lot of people said it couldn’t be done. A two hundred-foot-tall robot just wasn’t practical, they said. Well, you know Roman Turbo has never stopped at what was practical, and after hand-picking the best people in their fields–” he extended an arm to the mechanical and electrical engineers, computer programmers, and weapons specialists that made up Aki’s team–“we made it happen. No more will we have to schedule our lives around the whims of the Aquarian beasts, cleaning up after them, letting them run our lives. No! Now we can stand up to them. They push us around? We can push back! Ladies and gentlemen . . . I give you . . . MECHANDROMEDA!”

The banners parted like curtains. Spotlights switched on, turning the already-shiny surface of the machine to mirror brightness. Mechandromeda stood so tall that even those in the back of the crowd had to crane their necks to see her in her entirety; she had the sleek curves of a Ferrari, the greaves and breastplate of a Valkyrie, and the coppery, immobile face of Frédéric Bartholdi’s mother. “This new Statue of Liberty,” Turbo said, “will strike the first blow to free us from our complacent dependence on the monsters from the sea.”

Cheers erupted from the crowd; Aki smiled. He was working on the tracking side, but it had still been satisfying to be part of such a large undertaking, and to see the titanic machine gradually take shape before making her public debut. Turbo continued describing the machine’s features in admiring terms: “Mechandromeda is a fully remote-operated defense platform: we can pilot her without putting human lives in danger, and she has state-of-the-art onboard artificial intelligence to maximize efficiency in her movement, or if communications are cut off. She’s so smart she can practically drive herself!”

Aki’s mind drifted as Turbo began describing Mechandromeda’s considerable arsenal–he knew all about the technical specs, having sat through many meetings and presentations going over those details–and he found himself fingering the ring that he still carried in his pocket since Sachiko had returned it to him. Without even being conscious of it, his mind returned to the day he had given it to her.

Spica, another of the Aquarian beasts, had emerged off the coast that day, and Aki had (correctly) predicted that it would remain in place for several days. A gigantic crustacean-like creature, Spica spent all of its time with its back humped above the surface of the water, allowing an ecosystem to form, like a floating island. During the time it had drifted offshore, shedding coral-like scales from its underside that would become the basis of new reef growth, people from the city had visited its back and enjoyed the scenery and pleasures of a tropical island. Aki and Sachiko had climbed the “mountain” that had formed around its main dorsal vent and savored the bananas, pineapples, and other tropical fruit that grew in the verdant soil atop Spica’s shell. As the sun set, casting a golden light over flowers that could never have survived the Northwestern weather all year round, Aki had given Sachiko the ring and asked her to marry him. It was the happiest day of his life.

Until now, that is. He let go of the ring and clenched his fist, shutting out the memory: you can’t live on dreams and pineapples forever, he told himself. Now he was part of something bigger than himself: this was real. He had a purpose, one that would serve all of humanity.

“So you can see,” Turbo finished, “that the next Aquarian beast to breach our borders is going to be in for a surprise!” The crowd, stirred by his anti-Aquarian rhetoric, roared its approval. “In fact, I’m told that one is due to emerge any time. Would you all like to see this gal take care of some business?” The invitation had the desired effect as the gathered throng erupted again.

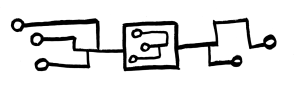

Without being referred to specifically, Aki felt the thrill of being at the center of the action: it was he who had, in his own way, set the schedule for Mechandromeda’s completion and unveiling. Tracking the Aquarian beasts in their circuitous migrations around the globe, he had predicted that the beast code-named Aldebaran would make landfall this day, most likely in the late afternoon. Moving swiftly to the tracking station next to the stage, he saw that his prediction was about to be confirmed: on a screen displaying a map of the coastline, a blinking light several miles offshore indicated the arrival of something big. It had to be Aldebaran, and it would be there soon.

From his vantage point in front of a bank of monitors, Aki and the rest of the team observed Aldebaran emerge from the sea and crawl into the area where Regulus and Antares had converged months before. Aldebaran resembled a giant slug, its back dotted with innumerable quills, each tipped by a single luminous globe. As it slowly slid forward, it left behind trails of gray slime that quickly hardened into streets and sidewalks. To mark its territory, it plucked its quills with tendril-like pseudopods that lined the perimeter of its vast footprint, and planted them at intervals alongside the trails, where they would become street lights.

“Gentlemen, there is your target,” Turbo said to Mechandromeda’s operators, a pair of technicians in a similar booth next to Aki’s. “You may proceed when ready.”

With practiced control, the techs directed Mechandromeda forward. The huge robot stepped forward into a cleared corridor, to the accompanying oohs and ahs of the people. The ground shook under her tread. When she reached the perimeter of the cleared area, she paused. A synthesized voice, feminine and mellifluous, projected from onboard speakers and was relayed through the PA system for the benefit of the crowd: “Attention Aldebaran. Return to the ocean at once. You are no longer welcome here.”

Aldebaran gave no sign that it understood or even heard the robot’s command. “All right,” Turbo told the operators, “give ‘im a nudge.”

“Shall we use the missiles, sir?”

“Let’s start with the repulsors. They need a good field test.”

The operators nodded and relayed their instructions through their bank of controls. Mechandromeda raised one arm, palm out, in the universal “halt” symbol. And then . . . nothing happened.

“Well?” Roman Turbo folded his arms impatiently. Mechandromeda stood completely still. Meanwhile, Aldebaran continued planting lights along the streets it left behind.

“We’re trying, sir,” one of the operators said, repeatedly tapping the touch-sensitive screens. “She’s not responding.”

“The onboard A.I. is drawing a lot of power,” the other tech said. “She’s locked us out!”

“Well, get back in there. We can’t let her go rogue!”

The synthesized voice spoke through the PA system again. “Mister Turbo?”

Surprised to hear himself addressed by name by the giant robot, Turbo stepped forward and spoke into a microphone. “Er, yes? This is Turbo.”

Her voice still projected to the entire crowd, Mechandromeda said, “Is this really necessary?”

Gobsmacked, Turbo covered the microphone with his hand and said, “She’s been hacked!” Controlling himself, he spoke into the microphone, “What do you mean, ‘necessary’?”

Mechandromeda lowered her arm. “I have calculated that non-violent solutions are 99% more likely to result in optimal results. Shall I stand down in order to minimize loss of life and property?”

Turbo was speechless. It was starting to sink in that the machine was talking back to him. The operators continued to press buttons and mess with the controls, to no avail. Finally, Turbo sputtered, “Stand down!? No, I want you to blast that sucker!”

Another pause. Aldebaran, oblivious to the drama surrounding its presence, began to slink back toward the ocean. One of the techs threw up his hands in exasperation. “It’s not outside interference. The A.I. has taken complete control. We’re totally locked out.”

Mechandromeda hadn’t taken another step. She seemed to be examining herself, for the first time aware of her own nature. She held her golden hands in front of the multi-spectrum camera sensors that were her eyes. “My maintenance history indicates that I was built at great expense, and with many irregular cost overruns,” she observed.

“Shut off the PA!” Turbo hissed to his technicians, already scrambling to do something in the face of this rebellion. “Uh, only the best for you, baby,” he said into the microphone.

“My positronic brain is available to calculate a more rational budget,” Mechandromeda continued. “The resulting efficiencies could be directed to improving the wages and working conditions of your employees.”

“Now you listen to me, missy–I built you!” Turbo shouted into the microphone. “Get that PA off!” Turbo bellowed to the flustered techs, “and get her under control!” The crowd began to melt away, muttering, bored and unsatisfied. They were starting to slip away from Turbo’s control.

Mechandromeda continued, oblivious to the tantrum Roman Turbo was throwing in the control room. “According to my calculations, the steel in my construction could have been used to add a light rail component to already-existing public transportation infrastructure. . . . And have you considered the benefits of raising the minimum wage? I would like to discuss the possibility of switching to a single-payer healthcare system. . . .”

Aki sat at his screen, watching the blip that represented Aldebaran moving farther and farther away, long after Roman Turbo had given up trying to coerce or reason with his defiant creation, long after the crowds had left, and long into the night, as Mechandromeda continued exploring aloud the implications of her sudden political awakening.

“She is beautiful, in her own way,” Sachiko admitted. She and Aki stood on the same balcony from which they had once watched the convergence of Regulus and Antares. Now Mechandromeda stood on the beach, gently stroking Regulus’s neck and scratching behind his ears with her metal fingers. The sun was beginning to set, adding a reddish hue to the robot’s brilliant golden skin and casting long shadows over the city. Beyond them stood the skeletons of new skyscrapers, built by Mechandromeda with the cooperation of human crews.

Aki only shook his head and smiled. He wasn’t watching the two giants on the beach; he stared into Sachiko’s deep brown eyes instead, and saw in them everything he wanted. Now that he no longer worked for Roman Turbo, he didn’t know what the future would bring, but he knew whom he wanted to spend it with.

“Do you think he’ll ever come back?” Sachiko said as they both turned to watch the great reptilian beast head back out to sea. The Aquarians had made fewer and fewer visits in recent months, and Aki had extrapolated the data as far out as he could.

“No . . . at least not in our lifetimes,” he said. Mechandromeda stood, as she had since her arrival, looking out to sea and watching with them. “I’ll miss the Aquarians,” he admitted, “but I have hope.” The sun dipped below the horizon as the last of Regulus’s dorsal plates slid under the surface of the water. “The city has a new guardian now.”