You can read Parts One and Two here and here.

As far as shared worlds go, it doesn’t get much more eclectic than superhero comics: just as an example, the three most recognizable characters in DC’s universe are an alien from another planet, an Amazon warrior with ties to the Greek gods, and a self-made vigilante, illustrating nicely the superhero genre’s connections to science fiction, mythology and pulp adventure. It helps to realize that Superman, Wonder Woman and Batman were not originally invented with the idea of coexisting in the same world, but grew organically in their own books, developing their own identities, casts of characters, themes, and locales before anyone thought of teaming them up. It was only later that the tangles of continuity across different books had to be cleaned up and what were often spur-of-the-moment inventions rationalized and codified.

Beyond the editorial offices of DC and rival publisher Marvel (and to a lesser extent Charlton, Fawcett, and the other small publishers that would either fold or be absorbed by DC), the first serious considerations of comic book worlds and how they were put together were written by fans, for fans. The comics fanzine Xero emerged in 1960, and more were to follow. Fanzines and amateur press publications have largely moved online since the rise of the internet, but organized fandom used to leave quite a paper trail, spread by word of mouth and united by newsletters, fan clubs and conventions, often advertised in the comic books and science fiction magazines where like-minded readers would be most likely to find them. Many of the fan writers would go on to work in the industry: Roy Thomas and Mark Gruenwald were both superfans who had in common an encyclopedic knowledge of characters and plot points that they would build on in their own stories for Marvel in the 1970s and ‘80s. Gruenwald had even made his name with a self-published thesis on comic book universes and their interconnected nature.

Even when writing about comic books began to enter the mainstream, it was still written from the point of view of a comics reader rather than a disinterested outsider. Jules Feiffer got the ball rolling with The Great Comic Book Heroes in 1965, a critical history of comic books in the 1930s and ‘40s mixed with Feiffer’s memories of reading comics as a child and working in the industry as a young adult; All in Color for a Dime, edited by Dick Lupoff and Don Thompson, was published in 1970, collecting a number of essays, including Lupoff’s own “The Big Red Cheese” (about Captain Marvel) from that first issue of Xero; and so on.

Feiffer, of course, was the long-running cartoonist in The Village Voice and had counter-cultural cachet; Lupoff would make his mark as a science fiction author and scholar of (among other subjects) Edgar Rice Burroughs; Thompson, with his wife Maggie, founded the influential Comics Buyer’s Guide. Authoritative as their essays are, one of their chief values is in putting the reader in the shoes of a young kid encountering Superman or Captain Marvel for the first time, seeing the characters through their eyes and accepting them on their own terms. But such is almost always the way, especially when pop culture subjects are involved: the first writing on jazz was descriptive, by journalists rather than musicologists, and the first jazz discographies were written by aficionados to aid fellow record collectors. Scholarly writing would later lag behind journalists and fans of rock and hip-hop as well.

A Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics, edited by Michael Barrier and Martin Williams, appeared in 1981, by which time scholars were taking note of comic books and it was more common for books on the subject to disentangle history and criticism from the personal and anecdotal. A Smithsonian Book may not have been the definitive volume on the subject, but it certainly seemed so to me as a young teenage comic book reader encountering it for the first time. Of course, more than the scholarly apparatus it was the reprints of comics from the “Golden Age” (up to 1954, the date of the adoption of the Comics Code by the industry) that made the book so valuable and enjoyable. I had been collecting superhero comics for a couple of years, starting with reprints of Stan Lee’s and Steve Ditko’s Spider-Man in the pages of Marvel Tales and gradually getting into the current stuff from there; reading about the storied history of Marvel and the Distinguished Competition made me feel like a real newbie, but the truth was I had been reading comics most of my life.

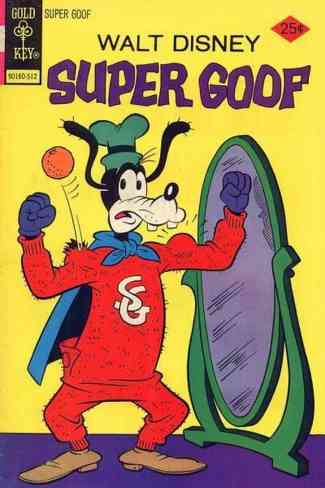

Before middle school, when I was younger than ten, most of the comic books I read were licensed “funny animal” books starring the Looney Tunes or Disney characters, and were often more far-ranging and imaginative than you would expect: Did you know Goofy had a side career as a superhero? If you read Super Goof you did! Just as Floyd Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse strips gave its title characters a sense of scope and adventure grander than what could be shown in the short animated cartoons, so the licensed Gold Key and Dell comics expanded my young mind by showing the “further adventures” of characters I already knew and loved. And needless to say, I enjoyed the Uncle Scrooge comics of Carl Barks long before I knew who Barks was, having a particular fascination with the evil duck sorceress Magica de Spell: who was this vivid character whom I had never seen in an animated cartoon? Why would Walt Disney (for of course I thought that’s who drew all the comics—he signed them, didn’t he?) create such a great villain and not use her in a movie? Why did all the Disney characters have such complex, fulfilling lives offscreen?

Oddly, when I graduated to more “mature” (or so I thought) comics, I completely discounted the funny animal comics I had cut my teeth on, and got rid of them completely. This isn’t an unusual experience by any means: most of us go through at least one phase where we clean out all the “kid’s stuff,” only to regret it later. What separated my later comics habit from my funny animal years wasn’t just the subject matter—there were some Twilight Zones, Archies, quite a few issues of Mad and Cracked, and even some superhero books mixed in with the comics I threw out—but my self-consciousness that I was collecting comics, that I had to keep them organized, follow a checklist, fill in gaps in my knowledge, and basically keep up: all the demands of fandom. Before that, comics were acquired at random (sometimes brought home by my parents when my sister or I was sick), often in one of those packs of three miscellaneous comics in a plastic sleeve (you could see the covers of the two on the outside, but the one in the middle would be a mystery, and may or may not have anything to do with the other two). That’s how we ended up with a bunch of Spire Comics’ gospel-themed Archie comics, basically church tracts starring the Riverdale gang. Except for a few favorites, they were equally disposable, in the tradition of pop culture since the dawn of mass production, and the ones that didn’t completely disintegrate wound up unceremoniously dumped in a cardboard box, a sort of comics slush pile.

A Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics helped me make connections between my undiscriminating childhood and my status-conscious adolescence. It taught me Carl Barks’ name and helped show me that his talking duck characters weren’t just for little kids; it introduced me to the original version of Captain Marvel, before DC ensnared publisher Fawcett in a crippling lawsuit over his supposed similarities to Superman; it let me connect the name Basil Wolverton to the grotesque caricatures I had already seen occasionally in Mad; it introduced me to the ambitious and insightful work of Will Eisner in The Spirit and the breadth of E. C.’s output before the comics panic of the ‘50s and the Comics Code forced them to cancel everything but Mad; it made me unable to see Marvel’s parodic Forbush-Man without thinking of the similarly attired Red Tornado from Sheldon Mayer’s Scribbly. It would even, much later on, form a foundation for me to understand what the heck was going on in the historically-informed comics of Tony Millionaire and Art Spiegelman.

Aside from giving me some ammunition if I’m ever cornered by Harlan Ellison, the Smithsonian book provided a great deal of entertainment and enriched my appreciation of the current books I was reading. My adolescent comic book collecting in the 1980s coincided with a period of reassessment in the superhero world: Superman’s fiftieth anniversary would be celebrated in 1988, and (perhaps not coincidentally) fifty years of world-building and cross-referencing would be consolidated (or swept away, depending on your perspective) in 1985 by DC’s Crisis on Infinite Earths, clearing the decks for a “fresh start” for Superman and company in the first and biggest of many company-wide “reboots” to come. The complexity of DC continuity included a number of parallel worlds, including separate universes for the Golden and Silver Age versions of characters, introduced to explain how Superman could fight saboteurs during World War II and still be a young man in the 1960s. It was simple, really: there was an old Superman in one world and a young one in another, and sometimes they would break down the barriers between universes and team up. Captain Marvel even came on board in the 1970s, at first in his own world (“Earth-S”) and later woven into the fabric of the DC universe as other characters had been before him (although he started going by the name Shazam to avoid confusion with that other comic book company).

The 1980s were also truly DC’s decade on screen, especially for Christopher Reeves’ iconic portrayal of Superman, but not overlooking Lynda Carter’s Wonder Woman on TV and the truly game-changing 1989 Batman directed by Tim Burton and starring Michael Keaton (many fans have cooled on Burton’s Batman in favor of Christopher Nolan’s grittier trilogy, but it’s hard to overstate what an event the 1989 film was at the time). By comparison, Marvel’s best-received screen adaptation was The Incredible Hulk in the early ‘80s.

I don’t bring up Crisis or Burton’s Batman to make comparisons with DC’s New 52 or to point out Marvel’s current domination of the big screen. The contrast speaks for itself, and more importantly the industry has changed greatly: one’s preference for a particular era of comics says as much about one’s age as it does about one’s taste. I’m thankful I stopped collecting before the huge boom of the early ‘90s—otherwise I might be burdened by nostalgia for foil-stamped hologram covers, oversized guns, and costumes festooned with pouches! Nor do I want to say things were better then just because I was younger: Crisis on Infinite Earths pissed off plenty of comics fans, myself included. I liked the alphabet soup of parallel worlds and twisting timelines in the DC multiverse. It irritated me to see whole settings and storylines erased from official existence. On the other hand, if I were an editor or writer, chained to stories that had been written decades before, I might have felt differently. Still, good writers had ways of getting around that, and a good story trumped pedantry any day.

And of course the characters who had been written out came back: Supergirl came back. Titano the Super-Ape came back. The Huntress came back. Kamandi and OMAC and all the rest found ways back in, sometimes in different places and sometimes greatly changed, but eventually they came back. And when Superman himself died, and it turned into a media frenzy, comics readers just nodded sagely to each other and knew it wouldn’t be permanent. He’d be back. Just ask Captain Marvel.

(Continue to Part Four)