Most artists like to talk about their creative work: they give interviews, write program notes, or even try to share their knowledge through teaching or writing how-to books. It’s a different matter, however, to get across one’s ideas about the urge to make art, or the creative process itself, within an actual artwork. To some degree, every work of art has something to say about the way it was conceived and constructed, but it’s not always obvious without knowing the artist’s work intimately and/or spending time decoding the work. At the other extreme, not every look at an artist’s life (including many autobiographies) has anything meaningful to say about where artists get their ideas or the inner resources that they draw on to face artistic challenges.

Within the somewhat rarefied field of “artwork that says something about the creative process,” I have a few favorites that have been important to me. Some I’ve mentioned previously in this blog; most are centered around an artist actively creating, either as biography or autobiography, yet all have qualities of fiction, even if based on a real person. Indeed, no one’s life is a perfect vehicle for a statement about art: there are too many accidents and interruptions to line up neatly with any particular theory. Yet, on the other hand there are often real-life coincidences and symmetries that would be too far-fetched if part of a completely fictional life. In the spaces between mundane fact and pure fable, the writer or artist is able to express their own viewpoint.

(As an aside, I wonder if this is why there have been so few satisfactory depictions of the Beatles as characters? There was hardly a single day of their professional career that went undocumented, and their every utterance has been recorded and examined closely. Is there any room for them to be reconceived in a fictional context without doing violence to the record?)

Fidelity to the facts isn’t a primary concern for Amadeus, the dramatization of composer Antonio Salieri’s supposed plot to eliminate his hated rival, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. As much as I love Milos Forman’s 1984 film, it is in some ways too successful: like the best period films, it wraps its characters in the physical trappings of their time, drawing us in and convincing us, through dramatic means, that it must have happened just this way. For the last thirty years, musicologists have diligently corrected the many misconceptions spawned by the film (which is not always a bad thing, if it leads to fruitful discussion and understanding the difference between art and history).

Peter Shaffer’s 1979 play, the basis of the film, is much more clearly using historical figures as an allegory for the contest of mediocrity and genius. As for Salieri’s role in Mozart’s death (a myth that may have had its roots in Salieri’s dementia in his later years, and which before Shaffer was dramatized by Pushkin and others), it might as well be Cain and Abel, or Jacob and Esau: it is the mythic resonance, the archetypal conflict, that interests Shaffer, not documentary accuracy.

I’m not sure what, if anything, I’ve actually learned about creating art from Amadeus, but it does speak to the reality that talent is spread unevenly in the world, and that wanting to create isn’t enough. Salieri’s desire to be a good composer, and a good man, to speak for God, isn’t enough, isn’t even relevant. “Was Mozart good?” he asks. “Goodness is nothing in the furnace of art.” (Again, we don’t know if the real Salieri said anything of the kind, or how he even felt about Mozart; but haven’t we all felt like the fictional Salieri at one time or another?) On the other hand, one could take from Amadeus the lesson that even for the world’s Mozarts success isn’t guaranteed, that there will always be challenges even for the most gifted among us.

Sunday in the Park with George, the 1984 musical by Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine, is one of its composer’s most direct statements about the creative process, to the point that Sondheim borrowed the title of the song “Finishing the Hat” for his collected lyrics. The phrase has become a kind of shorthand for the endless labor and attention to detail necessary to create something out of nothing (“where there never was a hat”). In the context of the musical, it also stands in for the real life painter George Seurat puts on hold in order to complete his masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. All his subjects, and especially his model and muse, Dot, have lives and stories of their own, but to him they are largely formal elements, puzzle pieces to be fit into his great composition.

It’s not hard to see why Sondheim identified with his fictionalized Seurat: the precision and formal clarity Seurat brought to his pointillistic canvases is a good match for Sondheim’s hyper-articulate wordplay, and the fragments of speech that Sondheim pieces into a mosaic of conversation, Robert Altman-style, is a fitting counterpart to Seurat’s modular approach to form. Sondheim’s formidable talent for meter and rhyme elegantly sets up the Act I finale in which George marshals his subjects into the final form of his painting. (If anyone ever tries to produce Tetris: the Musical, I can think of no other composer for the job.)

Sacrifices of a different kind are entailed in Stephen King’s 1987 novel Misery. King has never been shy about sharing his view of writing—how many of his novels are about writers, and how many of his stories feature writers’ creations and alter egos taking on lives of their own?—but Misery is probably his ultimate (fictional) statement about the work itself (I assume: I’m far from a King completist). As his stand-in Paul Sheldon struggles to complete a novel for his captor, Annie Wilkes, King speaks directly about both the urge to escape into stories and many of the mechanical aspects of constructing and maintaining a narrative. I was struck by the observation that “there was always a deadline,” even for books written on spec: “If a book remained roadblocked long enough, it began to decay, to fall apart; all the little tricks and illusions started to show.” There is a time and a place for every creative work, and some can stay on the shelf longer than others; for some the phrase “strike while the iron is hot” is imperative. One hears about novels and operas written over the course of years, even decades, but that’s never been King’s style.

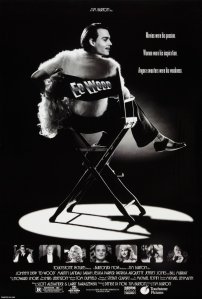

Director Edward D. Wood, Jr. has been called the “worst director of all time,” and his movies are memorably batty in conception and clumsy in execution. I don’t think he deserves that title (there are many worse films than his, and at least Wood’s work is entertainingly bad), but it’s unlikely that Tim Burton’s 1994 biopic Ed Wood would have had the same combination of humor and pathos if it were about someone more accomplished. The film takes plenty of liberties with the real Wood’s life, mostly concentrating on the making of Glen or Glenda? and Plan 9 From Outer Space. While Wood is the kind of outsider Burton has identified with throughout his career, it was Wood’s relationship to fading star Bela Lugosi that really attracted him to the material, reminding him of his own friendship with Vincent Price; I think it’s fair to read the movie as being more about Burton than Wood. The movie has an optimistic tone despite the ineptitude of its title character; it’s possible that Johnny Depp’s performance is how the real-life Wood saw himself, perpetually chipper and energetic in the face of constant failure. In any case, the goodness or badness of Plan 9 is beside the point: Ed Wood promises a look at the making of “the worst movie ever made,” but it’s really about the joys and frustrations of creating something, which is why it’s so relatable to anyone who’s tried.

Ed Wood also shows that no matter how much you enjoy creating, it’s impossible to predict how the finished product will turn out or how it will be received. If Wood’s work suffered from a lack of critical discernment, it’s even worse when self-criticism stops you before you’ve begun. That’s a central theme of Lynda Barry’s “Two Questions,” a short comic strip story that appeared in McSweeney’s and has been reprinted in a few places since then. “’Is this good?’ ‘Does this suck?’ I’m not sure when these two questions became the only two questions I had about my work, or when making pictures and stories turned into something I called ‘my work’—I just knew I’d stopped enjoying it and instead began to dread it,” begins Barry’s story. The process by which she learns (and relearns, over and over again) to let go of those preconceptions, “to be able to stand not knowing long enough to let something alive take shape,” is one that I recognize, as I recognize the paralysis of engaging in judgment too soon. As Barry says in a note accompanying “Two Questions” in The Best American Comics 2006, “trying to write something good before I write anything at all is like refusing to give birth unless you know for sure it is going to be a very good baby.”

It’s probably telling that most of the works I’ve mentioned were published or released during my teenage or twenty-something years, the age at which I was most engaged with honing my own craft and wrestling with what it means to be an artist. Which aspects of these stories affect me the most depends very much on the day and my own state of mind: sometimes I feel chained to the desk like Paul Sheldon (though not literally, thank God), praying for the tiniest bit of inspiration like Salieri or dreading the oppressing self-judgment of Lynda Barry’s two questions; other days I feel my creative juices flowing as freely as Mozart must have (my excitement tempered by the knowledge that Ed Wood probably felt the same way). At still other times I’m preoccupied with business matters, also touched on by these works. Perhaps that’s why I continue to return to them for inspiration and perspective: there’s an understanding born of experience in each one of them.

Do you have a favorite work of art that conveys the creative experience? Share it in the comments!